The Fall Guy

An easy, breezy romantic adventure that makes some passing gestures at the language of film and how it works, and some pointed ones at the role (and appreciation) of stunts within the larger production world, but not much else.

What is the point of the movies? Is it just glossy entertainment for the masses, ignoring artistic substance in favor of momentary emotional appeal? Is it real truth (or at least emotional truth) delivered inside a tasty outside but staying with us because of what it says about us? Or is it both? Even if it is, the sheer narcotic power of it seems to overcome any other positive aspect, not just for the endless individuals watching and writing about it, but the very people making them as well. Caught in jobs that chew them up and spit them out, and ask them to take less for doing so, the magic of the movies is so powerful even the people caught in the worst of its travesties can’t help but come back for more.

Colt Seavers (Gosling) can’t. After a terrible stunt gone wrong Seavers drops out of the business for good (he thinks) to focus on rehabbing himself and not being reminded of the thing he loved which almost killed him. Whether that’s the movies or the lovely camera operator (Blunt) he likes to flirt with is a question he’s not ready to answer yet. He’s so done with it all that the instant his old producer friend Gail (Waddingham) asks him for help he hops on a plane to Sydney to roll cars for Jody’s directorial debut. [Nevermind how she jumped from camera operator to director in just 18 months]. After climbing out of the burning wreck of a car Cole discovers he’s not been brought down to help with stunts but to find the film’s missing star before the film is shut down for good. And if he can rekindle his love affair with Jody and movie making, all the better.

There’s not much more to it than that. An easy, breezy romantic adventure that makes some passing gestures at the language of film and how it works, and some pointed ones at the role (and appreciation) of stunts within the larger production world, but not much else. Which is fine, Gosling and Blunt have such instant chemistry and charm that their scenes exist for them to be talking at each other and the fact that what they’re saying doesn’t matter … doesn’t matter. In the same sense that Colt’s various run-ins with dangerous Australian bodyguards is less about moving any story along and move about giving him a reason to perform a live stunt sequence the old fashioned way, or that the film Jody is agonizing over for emotional truth is a silly cowboy future-western space epic (raising the question of why the fake movies in ‘making of’ films are usually terrible?) much of The Fall Guy is about the happening and not so much what’s going on under the hood.

Which is a strange situation considering how meta the film intends to be, going to great lengths to show how the gags in films are done or the reasons for films to be constructed the way they are. As much as it reveals, it hides; it is a mystery after all. Going and looking for the wayward Ryder (Taylor-Johnson), Colt instead finds a dead body in a tub of ice and a group of increasingly violent mercenary’s trying to track him down and dispose of him as well, shattering poor Colt’s concentration every time he tries to figure out what is happening to him and how to get Jody back. They are, no matter how much The Fall Guy tries to jam them together, two extremely disparate throughlines which do not connect in any organic way and could have used a solid decision which is the focus of the film.

None of which is to say it is boring or unentertaining. It is none of those things. It’s also, except for the rare moments when Colt throws himself into a car to stop it or fights in the back over an overturned dumpster, rarely a Fall Guy movie, suffering through a split personality about what it wants to be. The effort to reconcile these halves slows action down in the end and drags things out to diminishing returns. What it is, is not that different than the weird sci-fi amalgam Metal Storm – something for which its makers have great affection but which ultimately its time has passed.

7/10

Starring Ryan Gosling, Emily Blunt, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Winston Duke, Hannah Waddingham, Ben Knight, Zara Michales, Adam Dunn, Teresa Palmer and Stephanie Hsu. Directed by David Leitch.

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare

Yes, there are times we go to the movies to see complex investigations of strange and compelling characters or themes opening up disturbing and unsettling ideas which we must spend time with and change us. And then there are times when we just want to see a bunch of evildoers meet grizzly ends because they are evil and deserve it. Which is to say, a Guy Ritchie film.

Yes, there are times we go to the movies to see complex investigations of strange and compelling characters or themes opening up disturbing and unsettling ideas which we must spend time with and change us. And then there are times when we just want to see a bunch of evildoers meet grizzly ends because they are evil and deserve it. Which is to say, a Guy Ritchie film. Sure, sometimes he feints towards complexity by casting his lens through men (and women) of low moral character, suggesting his stories are those of the under-dwelling and the dark things they do to one another which we’re better off not knowing about. But no. The villains are plainly marked, even within the depths of criminality, and the ends they will come to are clearly and obviously sticky.

And what better villains could there be, particularly for Ritchie, than Nazis? That’s nothing we won’t put past them and no level of violence we won’t enjoy seeing our heroes visit on them. Major Gus March-Phillipps (Cavill) and his hardy crew of saboteurs -- forerunners of the British SAS -- are going to try and find out if there is, alternatively shooting, garroting, stabbing, hatcheting, exploding and otherwise wiping German soldiers off the map in the early days of World War II. Their goal is a harbor in Western Africa where the German U-Boat fleet is being supplied from. With just a handful of soldiers, and no support from the British military, they are going to steal or destroy the German freighter guarded there and they will lie, cheat, steal and kill to get it done.

There is nothing unexpected about The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. The story could be written out in full, with every conflict, climax or plot turn expected from the first commercial. That’s a good thing. Or at least, not a bad thing. Nazis come along, they sneer and jeer, the heroes seem threatened and then just shrug and shoot them. It is cathartic in the extreme, like a gentle rain storm at night while trying to sleep, just with more bloodshed. At no point is there a question whether goals will be reached or if even a single member of the team will gain more than a splinter, no matter how skillfully Ritchie tries to feint. Not only is it impossible to imagine anyone being lost, more and more characters are added in as March-Phillips requires more and more help despite mowing down all resistance in front of him with relative ease. Why? Shut up, that’s why.

The point of it is in the small moments, the interaction between March and the cool-headed M (Elwes) sending him out to cause trouble, the small discussions of the trouble they will get into, or how they will impress their partners. The overarching story is set, immovable as a great stone. That leaves only the edges to play with so that is where Ritchie spends his time – cataloguing the German commanders’ horrors or Marjorie Stewart’s attempts to distract him – rather than worrying about things like danger or true conflict. Ritchie doesn’t want that and neither does his audience.

Which is fine. Comfort food is not meant to be complex, it’s meant to be comforting and Ministry is certainly that from its first bomb to its last shooting. A paean of English stiff upper-lippedness and underhanded criminality all put to a good cause. There’s nothing unexpected or surprising nor does it even feign there ever would be. It’s exactly what everyone expects and that’s all it needs to be.

6.5 out of 10

Starring Henry Cavill, Eiza González, Alan Ritchson, Henry Golding, Alex Pettyfer, Hero Fiennes Tiffin, Babs Olusanmokun and Cary Elwes. Directed by Guy Ritchie.

The First Omen

Fast, brash and intermittently nonsensical, The First Omen – a straight-laced prequel to Richard Donner’s horror opus – plays like a gussied up version of Blumhouse’s Nun franchise, with more body horror and slightly less cheap theatrics.

Fast, brash and intermittently nonsensical, The First Omen – a straight-laced prequel to Richard Donner’s horror opus – plays like a gussied up version of Blumhouse’s Nun franchise, with more body horror and slightly less cheap theatrics. Not zero; co-writer/director Arkasha Stevenson is not above throwing an item suddenly from offscreen or messing with her soundtrack to keep the audience off balance. But there is definitely a stronger focus on slow-moving horror of lost control, comparing the willful abdication of self-ownership that becoming a nun seems to require with the physical reality of motherhood. The view of child-bearing as transgressive and similar to a parasitic infestation isn’t new – Cronenberg has dallied with similar repeatedly – but Stevenson dares to take it to new, transgressive heights … until she remembers this is also an Omen film.

A prequel, in point of fact, picking up some two years before the beginning of the Richard Donner original. Rather than focus on the hijinks of childish Anti-Christ Damien, it focuses on the orphanage in Rome where he was born, and the strange forces at work which made that day possible. Introducing a pre-consipiracy Father Brennan who has just begun to learn of strange forces at work within the Catholic church attempting to bring the Anti-Christ into the world in order to force a disenchanted populace back to the church. At the center of the attempt are the nuns of an offbeat orphanage in Rome, recently joined by Sister Margaret Daino, a young woman raised her whole life in the church and preparing to take her vows. Her confidence is shaken, not just by Brennan’s words of warning, but by increasingly strange visions and dreams she encounters as she stays at the orphanage.

Like a secret Satannic bishop running a cult inside of an active church, Stevenson has many masters appease. On the one hand is her own particular point of view around what could be and is terrifying. On the other is the need to service story beat’s for a nearly 40-year-old franchise which ended its run in the 1980s. These don’t have to be two competing requirements, but it’s difficult for them not to be. The more The First Omen gives play to the latter – bringing in Father Brennan, explaining the Mark of the Beast and the cults secret plan, sending Margaret to comb for files and evidence – the more interesting first idea wilts and dies.

It brings with it a need to hold the audiences hand and guide reactions which works directly against the horror the film is trying to generate. The original Omen, coming in the wake of The Exorcist and a desire to capture that type of unsettling presence without the years of tropes attached to the genre to emulate, was crafted in the hands of a practiced Hollywood professional with no connection to the genre to be something cold and genuinely unnerving. It worked because of what it frequently didn’t do, adding power to the moments when it did do something. More than 30 years later there is an understanding not just that certain soundscapes and choices in the soundtrack – of those choir cues and chanting – would get the audience to the right emotional beat, but that the film should use them no matter what.

What’s left is a film which frequently tries to identify itself, but only does so when it gets out of its own way. When it does there are some gloriously disturbing moments that question what reality is for a large number of people. But it will as quickly turn to another very heavy handed horror film which can’t trust it’s audience to be truly disturbed, it needs to remind that this is a ride with guard rails and a set path. The time of The Omen has probably passed.

5 out of 10.

Starring Nell Tiger Free, Sonia Braga, Ralph Ineson, Bill Nighy, Tawfeek Barhom, Maria Caballero, Nicole Sorace, Ishtar Currie Wilson, Andrea Arcangeli and Charles Dance. Directed by Arkasha Stevenson.

Monkey Man

Simultaneously kinetic and thrilling, and long and drawn out, Dev Patel’s directorial debut Monkey Man is a study in contrasts, both succeeding wildly and falling short and frequently within the same scene.

Simultaneously kinetic and thrilling, and long and drawn out, Dev Patel’s directorial debut Monkey Man is a study in contrasts, both succeeding wildly and falling short and frequently within the same scene. Diving into the world of gratifying vengeance, Patel is an instantly accomplished action director and star, keeping his and our eye on his end goal no matter how dizzingly his camera and stuntmen move across the screen. But he also wants to dwell on the grief and suffering which drove Bobby to such desperate ends, and the Hamlet-esque inability to decide how far he is really willing to go. It’s a rubber band stretched tight, not so much in the manner of building tension as it is keeping either end from really moving. Like the Monkey Man he is a director at odds with himself, attempting to appease multiple masters and getting lost within his own world.

But what a world it is! A kaleidoscope of color, from the green earthiness of Bobby’s (Dev Patel) childhood to the neon-soaked excess of Mumbai, Monkey Man whirls through a miasma of sights and sounds. Bobby straddles both of those worlds, fighting in a monkey mask at an underground mixture of mixed martial arts and professional wrestling to make a bare living, but also working at a swanky nightclub where the rich and powerful come to indulge every vice available. It’s all part of a long term plan to give him the skills and means to get near the corrupt police officer (Sikander Kher) who burned his village to the ground. Like the Danish prince, when the time comes he’s not sure if he can pull the trigger despite the torment of constant flash backs to his youth. Instead he finds himself chased through the streets and buildings of Mumbai fighting his way through hallways, bathrooms, the back of police cars – anything which might stop him from reaching Rana again.

That level of existential confusion makes a lot of sense in an extended character drama or tragedy where the fact of the indecision is the point. In an action film its more of an irritant, an excuse to push off the promised conflagration and keep wheels spinning until the third act begins. There’s not a build from the point of the initial offense; Bobby knows what happened to his parents – he watched it with his own eyes – and has spent an extended child- and adulthood hampered by the extended rage it has left in him. Bits and pieces of it are related to us as he befriends the local drug dealer (Pitobash) and begins working his way into the confidence of the police captains associates, but not as attachment to some sort of great emotional breakthrough. It is information withheld until the form says it is time to unload it.

The same reluctance to act makes it difficult for Bobby to communicate with the world around him. He shares a few spare sentences with Alphonso the one-legged dealer or Sobhita Dhulipala’s indentured prostitute but not in any way that exposes his inner turmoil or what it means to him, only because it seems like what you would do. Patel is a good enough actor to hint at deeper rivers running underneath and as flavor to larger goings on it could create just the right mix of character complexity and extended heroics. But much of the time it is all that is going on and that makes the seams show.

It’s only after being severely beaten in his first attempt that Bobby returns to the jungle and makes connection with his spiritual namesake – the demigod Haruman – to stand against the empty preaching of the guru (Deshpande) who has been behind all of his trauma. It’s only then that Monkey Man comes into its own, shorn of all confusion. Once it stops faffing about and unleashes Patel on his adversaries, it’s easy to forgive a lot of the early time wasting. As a debut, Monkey Man is often thrilling and shows real understanding of the genre and what it could do and never has. If only he’d get to the point a little faster next time.

6.5 out of 10.

Starring Dev Patel, Sharlto Copley, Pitobash, Vipin Sharma, Sikander Kher, Sobhita Dhulipala, Ashwini Kalsekar, Adithi Kalkunte, Makarand Deshpande. Directed by Dev Patel.

Cabrini

Small in stature but big in heart and determined with a specific and heartfelt message, Cabrini is a classic studio biopic (albeit one not made by any studio) lionizing its subject and her accomplishments but also reminding us what is due each other as humans.

Small in stature but big in heart and determined with a specific and heartfelt message, Cabrini is a classic studio biopic (albeit one not made by any studio) lionizing its subject and her accomplishments but also reminding us what is due each other as humans. Diving into the American past, Cabrini ruminates on how far we have and have not come from using racism and prejudice against vulnerable communities and what can be done to help. Rather than lecture to directly on the present, it keeps its focus on the past, recounting the events of Francesca Cabrini’s (Dell’Anna) life with complete sincerity and not a hint of irony or judgment. It was what it was and that’s enough.

And what it was, was a lot. A lifelong missionary with a dream of one day heading to Asia, Cabrini is instead sent by the Vatican to New York where Italian immigrants have been demonized and ignored and struggle daily with poverty, joblessness, disease, and starvation. Diving headlong into the mess, and ignoring her own ill health, Cabrini works not just to bring food and medical attention to a population vilified by the community they live in, but to force that community to accept what is lying its feet. Ignoring hesitancy by the local Archbishop, ignorance by the press and outright enmity by political and financial institutions, Cabrini refuses to buckle. Instead, she drags reporters into the gutter to see with their own eyes how immigrants are living and threatens public shame on bankers and mayors to get policies changed. She becomes a living testament to a refusal to quit.

Yes, it’s a hagiography, but technically she is a saint so at least it fits. Director Alejandro Monteverde (Sound of Freedom) is not looking to make attacks against the system she was part of or find some controversy in her actions. There is no Christopher Hitchens “actually Mother Teresa’s zealotry kept people in poverty” here. Her story is held up as an example of how we should behave rather than how we do -- and not just to others, but for them. Compassion and determination go hand in hand for Cabrini, which means that any conflicts or roadblocks must come from the outside, leaving the nun herself exemplary but flat, never once facing a moment of self-doubt or hesitation. She’s an archetype, not a person.

Some of that is the nature of these kinds of film. They often run the risk of becoming a litany of events rather than realizations of the interiority of a person, and Cabrini is no exception. As with the sister herself, the film has so much to do there is no time to sit and ruminate or reflect, it must hurry ever onward to the next obstacle and the next and the next. Frequently it falls on the lead to fill in those gaps, suggesting certain levels of conflict and complexity that are absent in the text and Cabrini is no exception there either. Dell’Anna does just that, inhabiting her fully and dragging the audience with her like members of Cabrini’s own flock; she’s magnetic in the role, both aloof and alive, giving and closed off, a person and an archetype. Everything rests on her shoulders, but she is strong enough to carry the burden.

As many people have said, there’s no reason to reinvent the wheel. Cabrini doesn’t do anything any similar biopic hasn’t done and done recently, but it doesn’t need to. Monteverde is confident in his story and his star and he has every right to be. The real Cabrini, however much she may or may not have resembled this version, left her mark on prejudice and helplessness in a way we can all learn from today. This version of her life can’t help but hold some of that power, even if it doesn’t take many chances.

7 out of 10.

Starring Cristiana Dell’Anna, David Morse, Romana Maggiora Vergano, Federico Ialepi, Virginia Bocelli, Rolando Villazón, Giancarlo Giannini and John Lithgow. Directed by Alejandro Gómez Monteverde.

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire

Brash, loud, obnoxious and occasionally delivering what it promises, Godzilla x Kong – the fifth entry in Legendary Entertainments on going giant monster saga – throws every idea it has and then some into the blender but still struggles to create realistic stakes or characters to attach to.

Brash, loud, obnoxious and occasionally delivering what it promises, Godzilla x Kong – the fifth entry in Legendary Entertainments on going giant monster saga – throws every idea it has and then some into the blender but still struggles to create realistic stakes or characters to attach to. The argument could be made that the monsters themselves are the foci everything should be circling around but aside from a few character beats they are as static and cliched as the humans they are supposed to be protecting Kong and his compatriots are a means to an end rather than the end itself.

And that end is destruction in some of the most cartoonishly absurd action set pieces ever committed to screen. That’s a good thing. At a certain point director Wingard simply stops bothering with the forms of narrative and gives over to totally to the ridiculous, trying to find just how far is too far. Zero gravity monster battles? Freeze dragons? Pyramid battles and magic crystals? It’s all here, and then some.

A few years after Godzilla and Kong’s titanic battle the two have retreated to their own independent realms; Godzilla to travel the world fighting other errant titans, and Kong to the subterranean Hollow Earth looking for any hint of his own kind to end his eternal loneliness. When a rift opens in the cavern floor Kong abandons the Hollow Earth for the Hollower Earth, a larger prehistoric cavern filled with the missing Kong kind who had somehow been exiled centuries earlier when their leader, the Skar King, attempted to take over the surface world. Faced with the mixed bag of getting what he wanted and finding it trying to kill him, Kong has no choice but to team up with his old foe the King of Monsters who has been gearing up for the titanic battle he can sense coming. There is also a rock-n-roll giant monster vet, a mute psychic who can communicate with the monsters, a disgraced podcaster and a few more people who do not matter at all.

That’s not a criticism of Godzilla x Kong (well it is), just a statement of fact. The early days of the series when the monsters might emerge from the shadows for just a few minutes while the cameras remain trained on the humans trying to navigate the chaos … those days are gone. Gradually it has shifted, either to what it always had to be or what the producers at Legendary always wanted it to be … a Transformers-esque playground of destruction which uses its handful of human characters to relay necessary exposition and eat up the first hour of screen time because the visual effects budget won’t allow for 120 minutes of Kong and crew destroying things.

It sounds nihilistic because in some ways it is nihilistic. It is a literal boys’ toy room with children picking up their lizards and apes and smashing them into each other while making bang and crash sounds. It seems like they’ve started with the idea of Kong riding Godzilla’s back to crash into evil Kong and evil Godzilla and left the rest to work itself out till they get there. An argument can be made that’s all it needs to be, but that makes it all the more obvious what’s important in between as it sets up and sets up and sets up until Kong drops down a fissure and discovers his kin.

As much as it goes through the forms of a narrative film – following Rebecca Hall’s Dr. Andrews as she tries to discover what is affecting her adopted daughter (Hottle) and making the decision to head down to Hollow Earth herself – it’s clear Kong is where the filmmaker’s hearts are at. He has real pathos in his loneliness and more when he discovers the only ones of his kind are giant dicks that he’s going to have to fight rather than love. A full 30 minutes of the film is void of any spoken dialogue and yet as crystal clear in its character motivations as any action film ever made. (And suggests George Lucas was right when he said dialogue was just soundtrack, not storytelling, in cinema). Some of that is the simplicity of the characterizations themselves – Kong just has to re-enact any Eastwood western ever as he saunters into the layer of the bully to protect the child he has befriended. Dialogue would cheapen it.

And it wouldn’t matter. What matters is pink and purple skies and electric bugs and fights among the pyramids and giant monkey’s with robot arms. Looking under the hood would be counter productive. It just reminds you how much the human characters stand around saying why the monsters are doing what they’re doing – don’t ask how they know – because no one has bothered to explain it (despite showcasing that they can do so), or how little use the film has for Godzilla. He’s like a contractually mandated rock star, sleeping in his Italian apartment until it’s finally time to go on, doing his thing and then heading right back to sleep.

Like any piece of cotton candy, it evaporates and fades as soon as it touches the tongue. There is a sensation, a memory of something wonderful but it existed to briefly to be significant. It’s probably for the best; if the details were permanent it would be impossible to ignore how badly Godzilla x Kong has been slopped together.

5 out of 10.

Starring Rebecca Hall, Brian Tyree Henry, Dan Stevens, Kaylee Hottle, Alex Ferns, Fala Chen and Rachel House. Directed by Adam Wingard.

Ordinary Angels

Surface oriented and light weight, but with real humanity lurking with, Ordinary Angels takes the increasingly controversial stance that religious belief is all well and good but it’s ultimately up to human beings to look out for one another.

Surface oriented and light weight, but with real humanity lurking with, Ordinary Angels takes the increasingly controversial stance that religious belief is all well and good but it’s ultimately up to human beings to look out for one another. Keeping its heart on its sleeve and any proselytizing close to the vest, Jon Gunn’s is more of a character sketch giving Swank a chance at adult drama without any real cost or difficulty. It’s also completely willing to use real suffering as stage dressing for light drama but if Angels tells us anything it’s that sometimes you’ve got to bulldoze through inconvenient obstacles to get to the promised land.

Lost for years to the highs and lows of alcoholism, when hairdresser Sharon (Swank) finally gets on the wagon she is left with an addictive personality in search of a new focus to glom onto. It practically walks into the room in the form of adorable children (Mitchell, Hughes) mourning their mother, helping their father (Ritchson) keep things together and caring for the youngest who has her own fatal disease which can only be cured with a full liver transplant. Struck by their plight Sharon immediately barges into Ed’s life – despite his request for privacy – bringing plans for raising funds and organizing his community to cover Ed’s crushing medical debt.

A little bit of Erin Brokovich, a little bit of Sister Mary Benedict, Sharon is a force of nature and a fine performance for Swank to sink her teeth into. Blissfully unaware, or apathetic to, how she affects those she comes into contact with, Sharon barges on intent only on her own goals and desires even when those are about helping someone else. She refuses to take no for an answer from the stoic, conservative Ed – leaving Ritchson to mostly act with one syllable words – or the various organizations she bullies into helping. The screenplay by Meg Tilly and Kelly Fremon Craig (last year’s excellent Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret) is focused squarely on her and they bring life to what could be just a vague outline.

It is somehow simultaneously delicate and obvious. Ed’s troubles are real and so is Sharon’s concern. Their plight is deserving of the measure of effort she goes to. Even if Ed can’t and won’t see it, his mother (Travis) does. It’s not an accident that Angels comes most alive when they take over, forcing everyone around them to do the right thing even though it’s difficult. It’s also not an accident that the rationale’s for not doing the right thing are primarily internal leaving them unsaid and thus and unexamined (because it would be difficult to justify externally).

As the problems deepen, and Ed’s patience with Sharon’s meddling ways hit the breaking point, the retreat to alcohol raises its head again exposing her to the demons she has tried to run away from. Not just her desire for escape but how her addictions drove her own son away and the realization that the children she is helping, as noble as it may be, are a replacement in lieu of acceptance of her own flaws and real change in her life. Swank is empathetic and charming, partly because that’s what Sharon is by design, it keeps people from seeing something wrong with her, and partly because everything hangs on her shoulders. She wears it well.

Ordinary Angels could be a hopelessly sentimental sop, easily brushed off as ‘Hallmark-lite’, but there really is more to it than that. It ignores easy spiritual answers (in favor of easy physical ones) to remind how precious real gifts are. Yes it has a religious core but that’s not what it’s about. It’s about people helping people and that’s something that can always use celebrating.

Detained

Which is the hardest part of the long con: keeping everyone believing your lie, or remembering what was true in the first place?

Which is the hardest part of the long con: keeping everyone believing your lie, or remembering what was true in the first place? Both Rebecca Kamen (Cornish) and co-writer/director Felipe Mucci have the same problem, stuck in dizzying web of deceit so labyrinthine they themselves may have forgotten what their original truth was. Strong performances and committed actors make the most of a script which is more focused on twists and turns than internal logic despite being locked almost entirely in one location. Who is conning who and what do they want? Is it money? A baby? A confession. We may never know.

We do know, probably, that Rebecca, arrested in conjunction with a hit and run, will do anything to avoid going to jail or even being arraigned including threats, bribery and murder of her own. What seems like a routine bit of interrogation quickly turns on its head when convict gets their hands on a weapon and shoots one of the arresting officers (Bloodgood), offering Rebecca an opening for escape. Has she gotten incredibly lucky, incredibly unlucky or is something more sinister at work?

Trapped room films need strong performers and strong characters, usually with clear backgrounds slowly unfurling as we delve into what has locked everyone up together. (See for example, Branagh’s three recent Agatha Christie locked door adaptations, mysteries that exist to explain who its characters are and eventually the detective as well). Con artist stories, on the other hand, try to guard and hide its characters as much as possible in order to preserve twists and turns and not always to the benefit of logic and coherence. They are at direct odds with each other. That constant tension both drives Detained forward and keeps trying to tear it apart.

If it didn’t have as good a cast as it does, Detained might fly to pieces under the strain. As it is, Cornish holds sway bouncing with chaotic energy from victim to victor depending on the need of the scene and twists still needing to be revealed. It is a high wire act and a testament that she balances it so well, but also says something about the story she’s been thrown into. Bloodgood and Alonzo (a pair of not-cops on a time limit to extort money from her) play foil as much as they can but also have to balance their intentions with hidden motivations that warp and change like a chameleon.

Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. The constraints of the single room, often an enhancement for character study, work against the confidence game. Mucci works hard to keep the tension going with lots of ball juggling and twists and turns. The more you let it wash over you without thinking it through the better it gets. Like the faux-police station Rebecca finds herself in, too much attention exposes the cracks and flaws in the façade. The game is to keep anyone from being able to think, before the time runs out.

Perhaps if it were more of a straightforward character drama as interrogation scene or a completely free-wheeling long con it could work better. The pieces are all there for either version, but together they get in each other’s way. A strong cast keeps it working, perhaps better than it should. The next time out, with a more singular focus, could be something special.

6 out of 10. Starring Abbie Cornish, Laz Alonso, Moon Bloodgood, John Patrick Amedori and Justin H. Min. Directed by Felipe Mucci.

Argylle

Outsized, overdone and ill-conceived, Argylle takes what could have been a fun concept about mistaken identity amid hidden identity into a convoluted mess which consistently undercuts itself.

Outsized, overdone and ill-conceived, Argylle takes what could have been a fun concept about mistaken identity amid hidden identity into a convoluted mess which consistently undercuts itself. Is it a lighthearted spy film about James Bondian super-agent? A meta-fiction comedy about real life and fantasy becoming mixed together? An action fable about both? Yes, no, all of the above, none of the above … no one can decide or seems to want to decide leaving nothing but an incoherent blob which stays far past its welcome and can’t even make up its mind about an ending.

The beginning is pretty solid. Not the star-studded action set piece it wants everyone to think the story is, but the introduction to best-selling novelist Elly Conway (Howard), creator of the ubiquitous Agent Argylle. Despite being a notorious agoraphobe who never flies or travels without her cat, Alfie, and an overbearing, nit-picking mother (O’Hara) she has nourished a global fanbase waiting breathlessly for her next spy epic. When some of those fans turn out to be real spies willing to kidnap Elly to discover the plot of her next novel which seem to predict real world events with great accuracy. Her only hope against the sudden terrors she has spent her life protecting herself from is rambling, eccentric former agent Aidan (Rockwell) who needs what she knows as well.

And if it just stopped there that would be fine. Howard and Rockwell have strong chemistry and real comedic rapport. When nefarious agents of the Directorate attempt to abduct Elly from a train, Aidan’s sudden rescue attempt becomes a ragtag ballet of misunderstanding, bullets and screams. The more confusing the situation gets, and the more Elly attempts to escape, the better Argylle is. If it stayed that way throughout, slowly seeking out clues amid confusion and repartee, that would be enough. But no one knows to leave well enough alone.

No sooner has Elly escaped one confusing situation than she finds herself in the middle of more double crosses, rescued by her own meddling parents (creating the brilliant paring of Cranston and O’Hara) and intermittently hallucinating her own creation (Cavill) trying to give her advice how to survive her increasingly dire situation. It’s all a hat on top of a hat on top of a hat. Vaughn seems to have no faith in how long any situation can keep his audience’s attention, preferring instead to keep whipping the story around into new directions and then doing so again just as we’re getting used to the new status quo. It’s all built on the idea of reveal rather than revelation and forgets the law of diminishing returns.

The idea of Howard in an action-comedy gunning down evil doers is a good one, but it’s so covered in meaningless twists and turns it loses its power and becomes a chore. Eventually one that won’t end as ever more secrets are added on, even to the last moment. No one seems to know what it should be so everything is thrown at the wall desperately hoping for the final form to spontaneously manifest itself. It’s a waste of its main characters, it’s a waste of its imaginary characters and ultimately it’s a waste of our time.

5 out of 10. Starring Bryce Dallas Howard, Sam Rockwell, Bryan Cranston, Catherine O’Hara and Henry Cavill.

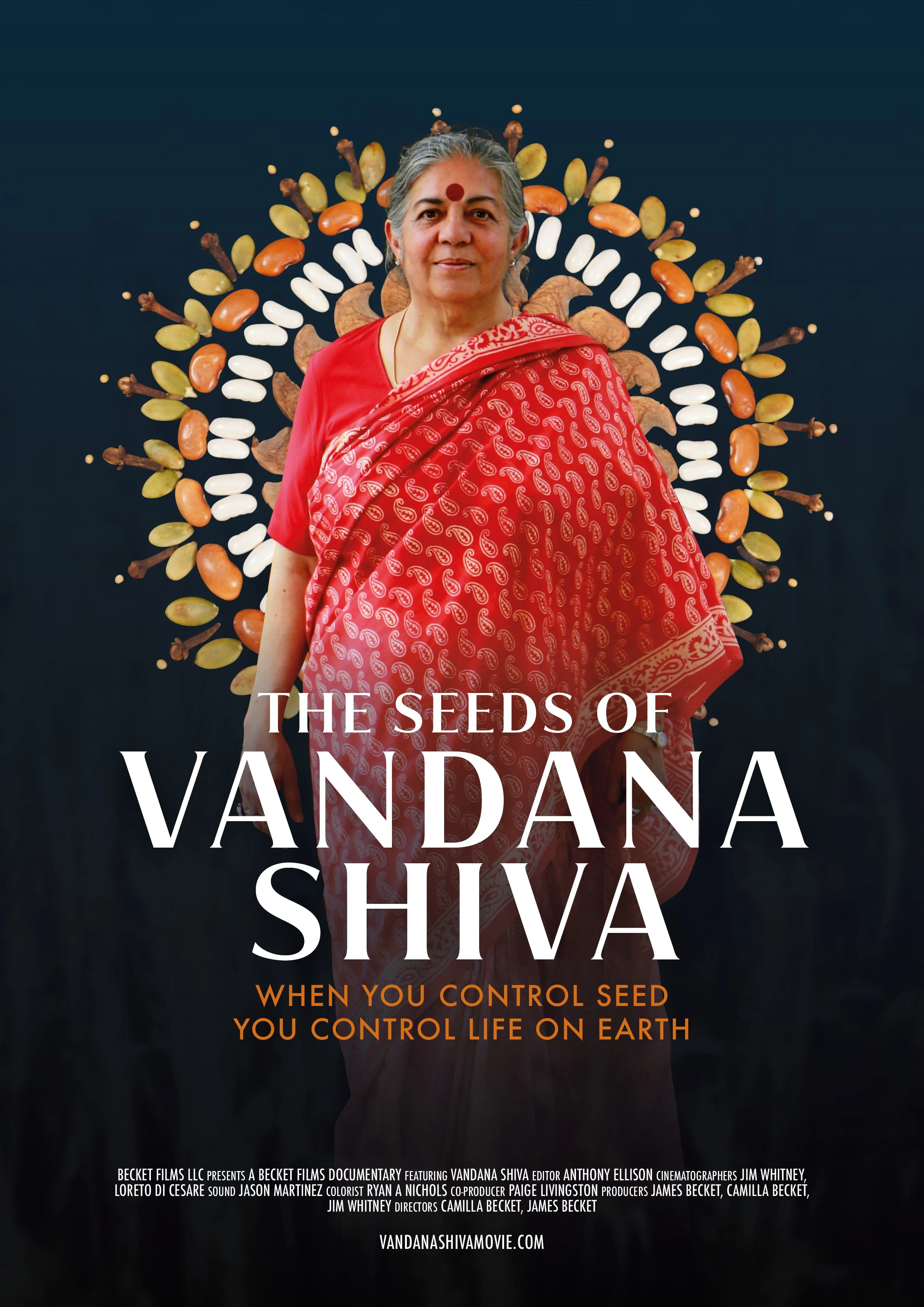

The Seeds of Vandana Shiva

Alternately insightful and off-its-rocker, wrestling with grand themes of colonialism, corporate greed and the roots of knowledge, Camilla and James Becket’s The Seeds of Vandana Shiva is ultimately interested in the complex question “can you be right about something even if you don’t know what you are talking about?”

Alternately insightful and off-its-rocker, wrestling with grand themes of colonialism, corporate greed and the roots of knowledge, Camilla and James Becket’s The Seeds of Vandana Shiva is ultimately interested in the complex question “can you be right about something even if you don’t know what you are talking about?” It’s not at all clear that’s the question the Becket’s know they are asking or even that it’s an issue at all, but it is at the heart of not just their film but the complexities of Vandana Shiva’s life and work, and the massive pushback she faces as she stares down global corporate forces.

An intellectual and activist, Shiva is a self-professed cross discipline didact trapsing across the fields of philosophy, physics and biology in a search for the connective tissue of all life. In the process she has run directly into the primary, extinction level crises facing mankind in the near future – climate change and food scarcity – and run them back to at least one primary root cause: corporate controlled, genetically modified food.

Across 20 years of activism, Shiva has opened a new front against global food control and particularly against agri-giant Monsanto which has won a number of high profile patent cases affirming that it owns its genetically engineered seed and whatever is grown from its seed (intentionally or not) while simultaneously using its corporate might and monopoly pricing power to force more and more of the worlds farmers to use said product. “It’s the East India Company, again,” a tribal elder tells Shiva as she tries to wake rural India to the danger creeping up on them and they are right. What government colonialism wasn’t able to achieve through centuries of war and plunder, corporate colonialism might just take with a few dollars, she warns.

It’s a piercing insight that others have made but not always with the perspicacity of Shiva, focusing as she does on agriculture companies that may not have the profile of Big Tech or Big Oil but are in many ways more fundamental to the changes currently happening on the planet, especially around soil erosion.

It’s also obscured by some of her other claims around what genetically modified food can and would do to the populace and its place in global climate change, which range from the interesting to the outlandish. Claims that she refutes less through pointed peer review and analysis and more by general explanation of her holistic study of the world and the way all of its structures are interwoven in a manner not all can perceive, as if she were the second coming of Carlos Castaneda. It’s an interesting point of view and picture of a strong-minded figure in the scientific and political world, one who for good or bad insists on taking on her opponents on her own terms.

The Seeds of Vandana Shiva does not take a particularly critical view to its subject’s claims, casting much of it as big agriculture opposition research designed to discredit a strident opponent and critique of their businesses. (Which it certainly is but that doesn’t make it false.). However, the Beckets are open enough in their coverage of her own claims and basis of belief – maybe because they believe, maybe not – to allow the viewer a deep view of Shiva and what she stands for and then make up their own minds. Many documentaries have never done so much.

7 out of 10

Directed by Camilla Denton Becket and James Becket

To Kill a Tiger

Late at night in the rural Indian village of Bero a young woman known as Kiran (not her real name) and her father Ranjit separately and together experienced one of the worst events that can befall a family when Kiran is accosted by several village locals and violently raped. It’s a reality which, as director Nisha Pahuja states at the beginning of To Kill a Tiger, is committed 10,000 times per year in India; an epidemic of sexual assault the country’s national and regional governments have been at a singular loss to affect in the face of local and systemic apathy.

Late at night in the rural Indian village of Bero a young woman known as Kiran (not her real name) and her father Ranjit separately and together experienced one of the worst events that can befall a family when Kiran is accosted by several village locals and violently raped. It’s a reality which, as director Nisha Pahuja states at the beginning of To Kill a Tiger, is committed 10,000 times per year in India; an epidemic of sexual assault the country’s national and regional governments have been at a singular loss to affect in the face of local and systemic apathy.

It’s one thing to see that calmly and directly written on a screen; it’s something else to see it play out in grueling reality over the course of years as justice is sought. Rather than try to move on and forget the assault Ranjit and his wife go directly to the authorities seeking justice, and quickly learning how great the obstacles to that are. Though the three perpetrators are easily discovered and arrested, no one in authority or even in the community is interested in what justice would require. Instead, Ranjit is pushed to marry his daughter to one of her assailants in order to reconfigure the attack as a marital dispute. Worse than Ranjit’s very logical cry “why would she want to marry someone who has assaulted her?” is the deafening silence which follows as the local government ministers clearly have no idea how to approach the problem beyond ‘get rid of it.’

Refusing to take the easy way out Ranjit pushes forward in a quest for justice. What he finds is incompetence and apathy in a staggering degree with a local government which falls back into byzantine rules (Ranjit can’t bring a case himself, a specific magistrate must do it and do it in specific hours on specific days, etc.) to insulate itself from what it and the populace around it see as an uncomfortable nuisance. The perpetrators themselves recognize the reality they are in, feeling emboldened enough to threaten those watching, as if their acquittal were a foregone conclusion.

In the face of this Ranjit and Kiran’s only choices are to quit and continue forward. As much as Tiger is focused on the systemic rot that makes such actions possible it is also a low key portrait in courage particularly of Ranjit as he presses forward with his case despite the stress, the wish that it wasn’t happening and a growing drinking problem. It is real courage, not the performed version of drama because it is without heroism recognizing it is not needed. All that is needed the will to continue on even as his long time friends and neighbors, and the government itself, try to just make everything go away.

As the village increasingly turns against Ranjit and his quest, demanding that he think of the villages reputation first and how people are talking about them because of the trial, unfortunate commonality with the worst of humanity raises its head. Similar to Ophul’s Hotel Terminus and its discovery of how many local French were perfectly happy to let Nazi collaborators return to their lives because “it was so long ago” and “why dredge up old memories,” the main goal of the everyday people is to put everything behind them and forget about it, not realizing that in their zeal to do that they are committing a sin almost as vile as the initial crime.

Similar to Ophuls, the filmmakers find themselves sucked into their own film as the populace also turns on them for daring to shine a light on Kiran’s plight, blaming those making noise (rather than the rapists themselves) for causing so much trouble to the point that filmmakers themselves must decide whether to go on and even offer cover to Ranjit before his final confrontation with the judge.

To Kill a Tiger is an intense, damning portrait of both society which supports violence and the gentile realistic bravery needed to combat it. A must see.

9 out of 10.

Directed by Nisha Pahuja.

Apolonia, Apolonia

What makes an artist? Not just the desire to create but the desire to do so above all else, the will to follow that impulse through and the luck to succeed. A lot of biopics have attempted to answer that question, usually by reciting the defining elements of their lives in an orderly progression of events, perhaps with some dramatics focused on at certain specific moments in time. They usually come to few if any answers because people are more than just the events that happened to them. Director Lea Glob was gifted with the opportunity to follow the life of an esteemed artist in the making, to watch them create themselves in real time over years and realize that she is asking it of herself (and the price to be paid for it), as well.

What makes an artist? Not just the desire to create but the desire to do so above all else, the will to follow that impulse through and the luck to succeed. A lot of biopics have attempted to answer that question, usually by reciting the defining elements of their lives in an orderly progression of events, perhaps with some dramatics focused on at certain specific moments in time. They usually come to few if any answers because people are more than just the events that happened to them. Director Lea Glob was gifted with the opportunity to follow the life of an esteemed artist in the making, to watch them create themselves in real time over years and realize that she is asking it of herself (and the price to be paid for it), as well.

Over the last 10 years Apolonia Sokol has carved out a niche for herself as one of the foremost new contemporary painters, focusing on figurative studies (frequently but not always women) in ambiguous moods and locations hinting at the depth of life in individuals beyond the single moments in time her canvases capture. Before that happened, however she was a struggling artist moving from city to city and gallery to gallery trying to find out what these figures mean to herself or to anyone else and if she even has something to say. And before that she was an intelligent young woman with a unique background, growing up in a small theater in Paris owned by her parents where she seemed destined to live a life in the arts. Was it because of her bohemian parents, because of the nomadic existence she lives after the her parent’s divorce, something deep inside of her from before birth, or none of those things?

Glob’s film knows better than to make any definitive statements but we can make some inferences. Sokol’s own parents, beyond putting her in the midst of creation as avocation from her youngest age also filmed much of her early life (including her conception and birth) to show back to her as an adult an give her a view on where she came from in a raw manner most wouldn’t. It opens a world to Glob, of Sokol as a young woman questioning what she wants out of life even as the foundation of her childhood is removed forcing her and her mother to relocate to Denmark. As an art student she is no different than any other 20 year old, primarily concerned with externalities like what will happen with her home, what will happen with her friend Oksana – a Ukranian ex-pat fighting against Russian aggression years before the actual invasion – and will she pass her exams.

Years later, having begun to navigate the fickle art world and its need of patronage to continue, she has become more than a subject for Glob. She is almost an anti-thesis, a woman who has turned her back on sort of domestic life – giving up any thought on children or family – to apply herself entirely into figuring out her creative self and how to make it work as a career and a life. Glob by comparison works with her husband and compares the difficulties of making that life work (including a very difficult birth that makes future children impossible) almost as a condemnation of Sokol has chosen to give up versus what Glob is forced to.

And yet she also clearly sees much of herself in Sokol as well as each focuses on portraits of women in an attempt to understand theme and the world. Gradually Glob finds herself drawn more and more into Sokol’s orbit like a real-life Persona, having conversations while Sokol bathes and even at one point training her own camera on herself while left alone in Sokol’s apartment. Is she making her film because Sokol herself is such an interesting person (yes) or is it to understand herself and the choices she has made in her life (also yes)?

Gradually, as real life always does, people move on. Sokol moves continually around the world, unmoored from life around her, following her muse wherever it takes her including fellowships and awards, as the the things which were once of paramount importance in her life fall away and are forgotten, suggesting perhaps they were not what made her such an interesting artist in the first place. Does Apolonia, Apolnia ever really answer its own questions? No, but not because it can’t, but because it realizes at the end that there is no answer.

8 out of 10.

Apolonia Sokol, Hervé Breuil, Lea Glob, Oksana Shachko and Alexandra Tlolka. Directed by Lea Glob.

The Beekeeper

To be or not to be,” a fluorescent coated, bottle blonde South African mercenary spits at the Jason Statham’s master beekeeper / special forces commando during their final confrontation. That mélange of ideas smashed into your face is all you need to know about David Ayer’s newest action film The Beekeeper or why you should see it. The only thing that could be better, and I hope it is true, is if each infinitive was actually spelled ‘bee’ in the script. (I’m just going to assume that it is and give it another point for audacity). That is the level of silliness at work and it really deserves to be seen to be believed.

“To be or not to be,” a fluorescent coated, bottle blonde South African mercenary spits at the Jason Statham’s master beekeeper / special forces commando during their final confrontation. That mélange of ideas smashed into your face is all you need to know about David Ayer’s newest action film The Beekeeper or why you should see it. The only thing that could be better, and I hope it is true, is if each infinitive was actually spelled ‘bee’ in the script. (I’m just going to assume that it is and give it another point for audacity). That is the level of silliness at work and it really deserves to be seen to be believed.

A revenge action thriller at heart no different than any other, Beekeeper posits a world filled with terrible people who view their fellow man as resources to be farmed like wheat or carp, and the only way to deal with such people is by force because legal and political systems can’t or won’t do it. Or at least they won’t do it in the thoroughly cathartic manner of hooking the worst person you know to a truck and driving him off a bridge at full speed. Even the government has accepted this reality, creating a group of ‘Beekeepers’ literally above the law whose job is to freelance identify and remove threats to the polity in the most direct manner possible. There is, as there has been with all of these since Death Wish, a troubling border shared with nihilistic fascism where might is the only thing that truly makes right and the only hope is that the ubermensch believes in morals and justice at some level.

Said superman here is, as he should always be, Statham: a former member of the secret Beekeepers who has retired to keep bees because (and this is true of everything in The Beekeeper) the metaphor he lives by is both figurative AND literal. There is no distinction between metaphor and reality, and if for one moment it seems like there might be Ayer and screenwriter Kurt Wimmer will blow it up. When the widower (Rashad) he is renting beekeeping space from loses her life savings in an internet scam Statham takes it upon himself to find the perpetrator and burn their business to the ground as well as anyone connected to it. Uncovering an increasing web of perpetrators leading up to the White House itself, and remembering the beekeepers maxim to run out damaged bees that endanger the hive, Statham takes the bees instinct as his own even if it means killing the President. And in between, many facts about bees are recited. If it turned out the script was 20 pages light and the filmmakers filled it in with excerpts from the Wikipedia page on bees, I would believe it.

Yes, it’s stupid. That’s a good deal of its charm. Considering how much of the film is bathed in neon and over the top nonsense it’s not a large leap to expect the filmmakers know it, too. When Statham finally finds the scammers they are not put upon keyboard warriors stacked in endless rows of cubicles but work in an a neon painted boiler room with club lights and EDM blaring over the speakers while an obnoxious crypto bro yells at them over a megaphone to steal harder. The villains are like reverse huntsman, painted in the brightest, broadest colors possible (the more neon the better) to make sure they easily identified. So when a fellow Beekeeper shows up to put Statham out to pasture and she walks around on stiletto heels with a purple mohawk and a minigun in the back of her truck the only response can be “sure, why not.”

It doesn’t make much sense, with only the smatterings of connective tissue and human beings who cannot react like any sort of human being or even notice how weird everyone around them is behaving. Recognizing the defects and the futility of trying to fix them, Ayer fills his screens with gifted actors who can ramble on nonsense with the best of them so that they can talk a lot about bees. If it was a bet to see how many times Jeremy Irons can be made to say the word ‘bee’ … then it was time well spent. The only one left on the outs is an insouciant Josh Hutcherson as the most entitled, ridiculous of crypt bros whose only job is to be imminently punchable but is not in the least believable as a villain.

Is it all really, really stupid? Yes. It is gloriously, wonderfully, joyously stupid. It may be the dumbest thing made this year. Everyone should see it immediately.

4 out of 10 (but really 8 out of 10)

Starring Jason Statham, Emmy Raver-Lampman, Josh Hutcherson, Jeremy Irons, Jemma Redgrave, Bobby Naderi, David Witts, Megan Le, Taylor James, Minnie Driver and Phylicia Rashad. Directed by David Ayer.

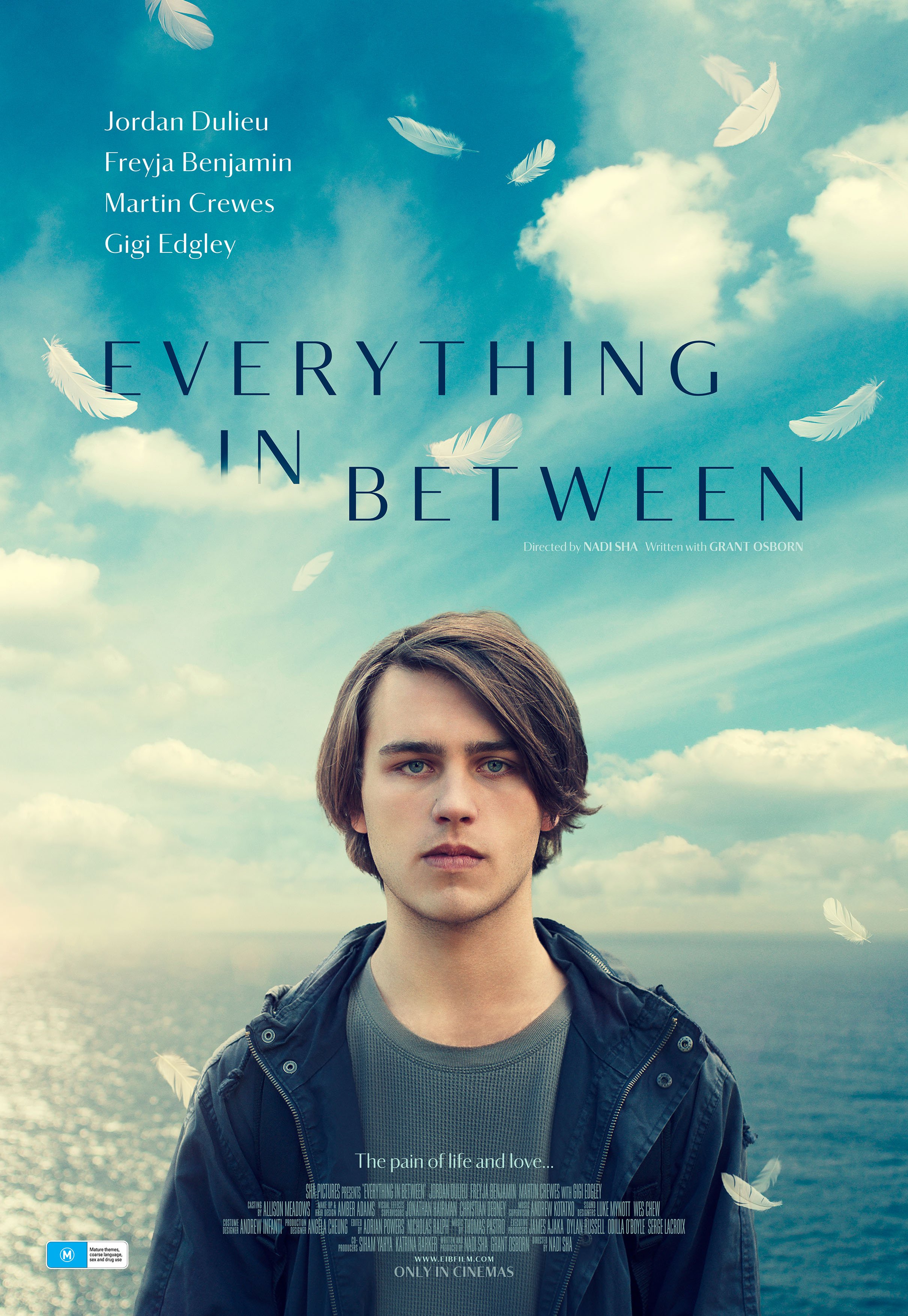

Everything in Between

Physicists tell us the world is mostly empty. What we perceive of as solid and real are in fact motes of being separated by vast distances between which the entirety of reality can pass without notice. And yet those burning singularities invariably become entangled, creating matter and form and the presence of a physical world. We're a compact of contrasts, both solid and empty, real and illusory. Nadi Sha's Everything in Between is a similar study -- sentimental but philosophical, thinly sketched but deeply complex, narrowly focused but uniquely universal.

Physicists tell us the world is mostly empty. What we perceive of as solid and real are in fact motes of being separated by vast distances between which the entirety of reality can pass without notice. And yet those burning singularities invariably become entangled, creating matter and form and the presence of a physical world. We're a compact of contrasts, both solid and empty, real and illusory. Nadi Sha's Everything in Between is a similar study -- sentimental but philosophical, thinly sketched but deeply complex, narrowly focused but uniquely universal.

It would be easy to think there's not much else to say about middle class ennui; it's been focus of western literature since the middle class evolved and of independent film since at least the 70s. David Knight (Jordan Dulieu) could be an escapee from any one of them, an introverted and lonely scion of comfortable but oblivious parents (Gigi Edgley and Martin Crewes) feeling isolated from the world around him, adrift in that infinite void between us. When an aborted suicide attempt lands him in the hospital he finds himself sharing space with the unmoored, untroubled Elizabeth (Freyja Benjamin) who takes life as it comes until she starts suffering from the symptoms of a strange disease.

On the outside Everything in Between sits too comfortably in the orbit of other, similar films that trod this similar ground. David, his primary needs covered his entire life and his parents oblivious to his need for purpose and inability to self-create it, and Elizabeth, a free spirit with a general, genial spirituality and little use or experience with the practicality of life, are primary constructs of the genre. Sometimes the bonding element is tragedy, sometimes it is comedy, sometimes it is the purely mundane. Everything in Between camouflage itself in those tropes before throwing its nighted colors off to expand its focus and try something new.

As Elizabeth's disease expands, David brings her home (she has nowhere else to) and into the path of his parents who are still dealing with the trauma of being pulled from their personal concerns, the opportunity for easy bathos expands but writer-director Sha easily squashes it. Instead, forced into close proximity and the gap between them diminished, what could have been flimsy sketches of characters expand to reveal inner lives. Elizabeth ignores the easy cloak of the manic pixie dream girl to reveal a frightened woman facing mortality at a young age and in no mood to become someone's fixation. Martin, a self-involved financier who hoped to brush off his son's suicide attempt finds himself offering up the support David has needed without entirely realizing it, while mother Meredith bristles at someone else taking over a role of importance in David's life and slowly realizes where she herself has pushed him away. As philosophical think piece on existence, Everything trends towards empty pop psychology but as interpersonal character drama it soars. The worse things get, the better Everything becomes.

It's a study in contrasts all the way down; waifer thin characters but deep and affecting performances (particularly from Benjamin and Dulieu), light thematic depth but complex family dynamics, straightforward scripting but confident and assured direction. Rather than getting lost within the great forest of independent bourgeois critique, Everything in Between stands on its own like a lighthouse saying something more, and better, about modern life.

Starring Jordan Dulieu, Freyja Benjamin, Martin Crewes and Gigi Edgley. Directed by Nadi Sha.

JazzTown

What is jazz? It’s difficult to say about any artform and more so about one born of improvisation and spontaneity. The very difficulty in defining it also makes it almost impossible to make any firm predictions on where it is going, how it will change into the future. That doesn’t stop director Ben Makinen from trying in JazzTown, his paean to the jazz scene of Colorado, but like the artform itself the answers he finds are frustrating and uncomfortable by design.

What is jazz? It’s difficult to say about any artform and more so about one born of improvisation and spontaneity. The very difficulty in defining it also makes it almost impossible to make any firm predictions on where it is going, how it will change into the future. That doesn’t stop director Ben Makinen from trying in JazzTown, his paean to the jazz scene of Colorado, but like the artform itself the answers he finds are frustrating and uncomfortable by design.

Part of that is because, as many of the musicians Makinen interviews explain, jazz is always evolving in a way few musical styles do. Whatever it started as, it is not that way now and whatever it is now, it will not be tomorrow. That uncertainty and surprise is part of what makes jazz what it is, not least because there’s no telling where it will emerge. Colorado in general, and Denver in particularly, are not generally thought off in the list of major jazz hubs, but in his several years chronicle of the local jazz scene there Makinen a culture and history as deep and intrinsic to the artfrom as anything from Chicago or Kansas City or New Orleans.

More importantly, and frequently with more sorrow, it’s a scene with a keen idea of where it sits in the jazz firmament and where the art form itself is likely going. Digging into the initial background of jazz in Colorado who is playing it there, JazzTown on its surface just seems like a series of interesting but brief interviews with local musicians offering up anecdotes about their time around the city and how they fell into form to begin with. Each small story, however, builds to a more interesting whole, creating a mosaic that when viewed from a distance defines and shapes the history of the town and offers a view on it (and its music) quite different from the standard expectation. In many cases artists just fell into it due to the draw of the rhythm and soon found themselves ensconced a life they may not have expected.

None of them, however, have any illusions about how that has been rewarded or what it means for those coming after them. More than one old hand takes the moment of the film to let whoever comes after know that it wasn’t worth it and to find something else to do with their lives. It quickly becomes a sad and depressing picture of cultural gentrification, one where the reality that there’s no way to make a living doing it leaves it only to future practitioners who don’t have to worry about making a living at it. The foresee a world where jazz is no longer created for casual audiences who stumble upon it as they had in the past, but something created only by a select group of musicians for a select group of musicians, an ouroboros continually feeding on itself.

Within that misery there are still seeds of hope. Makinen takes some time to focus on the next generation of musicians coming up, fully aware of where the form came from and how it has changed. A young drummer, not yet worrying about how to make money doing it, focuses more on how the sound has changed in reaction to other musical forms around it and reminding at the end of the day that it’s the sound that is heart of the form. As long as that still exists, in some form, jazz will never die.

The Country Club

The rich, they’re just like us except for their views on relative effort, merit, societal norms or achievement. With no outside desires driving them on their world revolves around keeping up their existing parasocial relationships (because in a world where everything is fake every relationship is parasocial) and maintaining appearances. The only thing they are good for externally is to provide resources to the hard working up-and-comers who are trying to achieve … in order to become just like them.

The rich, they’re just like us except for their views on relative effort, merit, societal norms or achievement. With no outside desires driving them on their world revolves around keeping up their existing parasocial relationships (because in a world where everything is fake every relationship is parasocial) and maintaining appearances. The only thing they are good for externally is to provide resources to the hard working up-and-comers who are trying to achieve … in order to become just like them. It’s a dynamic ripe for satire and if there is a failing to Fiona and Sophia Robert’s sly take down of country club culture it’s that it’s not weird enough.

The sisters Robert here are the sisters Cartwright, a pair of ambitious teens with great ambitions for what they want out of life but few resources to make it happen. The answer to their problems arrives in the form of a letter mistakenly sent to Elsa (Sophia Robert) who happens to share a name with the influencer daughter of a Connecticut blue blood family. Invited to a junior golf tournament, aspiring player Sophia sees a chance to win enough money for college while Tina (Fiona Robert) sees the opportunity to acquire investors to support her as a fashion designer. What they find is beyond their wildest imaginings, a world of petulance and expectation embodied in the beret wearing weirdness of Roger Kowalski (Higgins), a lost little boy who only cares about winning the tournament but doesn’t particularly care about playing in it.

A sly and witty screenplay by the Robert sisters is the engine that powers The Country Club, filled with small but perfectly placed side characters engendering just the right amount of weirdness. Like Caddshack and other class warfare comedies before it, the dynamic between the put upon club workers and their insouciant employers is its core. It’s a little constrained by a smaller budget and cast, putting most of that onto the shoulders of beleaguered Lumer (Ormond), Roger’s caddy and only friend who tries to satisfy is every whim even if it means playing for him during the tournament. It’s a lot to put on one character’s shoulders, alongside becoming the focus of Tina’s romantic attentions and he can’t quite carry it all but he also doesn’t need to. The Country Club wisely moves along to one of its more fanciful supporting characters to keep its more conventional aspects from dragging things down.

Director Fiona Robert shows a keen eye for filling those roles, from James Urbaniak’s sleezy club manager (who we could sadly use much more of) who loves nothing more than tormenting his assistant, to Magaret Ladd’s elder grand dame of the tournament or Elaine Hendrix as the domineering mother who answers many questions about why Roger is the way he is. Everything speeds along at a tidy 89 minutes which doesn’t give most characters more than exactly what the plot needs of them, but nor do they need it. Do we need to spend more than a single outing with chatty, self-involved Mary-Anne Montreal (Chow) or the handsome and self-involved Marshall (Levi) to get what we need from them? Not really. Familiarity really does breed contempt; any more time with any of them would have ruined the joke and increased the dullness.

In no one is that more obvious than Roger himself. Funny in small doses, Higgins’ pampered momma’s boy is less and less funny and more and more irritating the longer he is on screen. Not least because pulls attention away from the more interesting Cartwright sisters and offers little of interest in return as he slowly swallows the film whole. A cardinal warning of the old saying about less being more, Roger nearly derails everything interesting in The Country Club. It's not enough to hide the promise of future comedy outings from the Robert’s, just a hope that they leave buffoons in the background next time.

Starring Sophia Robert, Fiona Robert, John Higgins, Sean Ormond and James Urbaniak. Directed by Fiona Robert.

Discontinued

Alternately bleak and hopeful, Trevor Peckham’s Discontinued is a refreshingly original sci-fi take on addiction, maturity and the connective tissue of society that refuses to baby its audience even when it probably should.

Alternately bleak and hopeful, Trevor Peckham’s Discontinued is a refreshingly original sci-fi take on addiction, maturity and the connective tissue of society that refuses to baby its audience even when it probably should.

Picking apart the why’s and needs for society to exist, Peckham’s necessarily small mindbender plays with big ideas cunningly concealed within the clichés of other genres. Disaffected twentysomething Sarah (Hutchinson) could be mistaken for an escape from another, lesser comedy about a burgeoning adult who pushes society away because they are terrified of joining it. A lot of them have been made. All of that is pushed out the window, so to speak, when a charismatic hologram (Fishburne) appears on televisions worldwide to let everyone know the world doesn’t actually exist, it’s merely a computer simulation which will soon end. Everyone in the world, from Sarah to her parents to her therapist (Picardo) have to decide if they will be removed from the simulation and inserted into a permanent heaven where they will experience the most blissful moments of their lives over and over, or if they will decide to remain behind in a largely empty world which will likely gradually fall apart.

There are a lot of directions a story can go from that direction, from questions of what do those types of questions mean to how people respond to such a change in all they know. Discontinued is not dark enough to delve into Solaris-like existentialism or comedic enough to highlight a discussed but unseen descent into debauchery as consequence is removed from life choices. Like the proverbial terrorist forcing a stark character choice via explosives, the decision here is so starkly keyed to Sarah’s own disassociation with the world around her it could have been specifically engineered for her. And maybe it was.

Alone among anyone she knows, Sarah earnestly questions whether deciding to remain behind in quiet isolation isn’t the superior choice. Like Will Freeman she believes every person really is an island and likes it that way. Or at least she thinks she does.

Buried deep, deep (maybe too deep) within this is the reality of Sarah’s past battles with alcoholism and the reality that if the world hadn’t ended she was headed towards relapse. She systematically ignores her therapist’s advice to stop worrying about what she can’t control. That is, to recognize her powerlessness in the face of addiction, let go of a need for control and trust in a higher power. In this case the higher power just happens to be an artificial intelligence enabling self-actualization for its subject but tomato, tomato.

If the consequences do remain small, they are still surprising. Refusing to be pinned down by the easy narrative structure Discontinued masquerades in at the start, Peckham continually twists the narrative into unexpected directions in order to wear down Sarah’s prickly exterior. Rather than fill the time with interactions among friends and family heading to the final goodbye, Discontinued suddenly jumps forward into the empty world Sarah was pondering and find it to be not at all bad. That only lasts long enough for the obvious flaw in her desire to make itself apparent before Peckham changes perspective again. Discontinued always keeps you on your toes.

The lack of scale works against some of the large ideas Peckham is playing with and puts a tremendous amount on Hutchinson’s shoulders but she carries it off even weighed down by some early indie film cliché that should have died already. It quickly burns itself down to its essence, however, revealing a thoughtful and bracing thought experiment about the need for human connection and the ways we try to convince ourself it’s not real.

Wildflower

Heartbreaking, heartwarming, funny and grim, Mark Smukler’s feature adaptation of his short film, Wildflower is a fascinating glimpse into corners of life film usually leaves untouched

Heartbreaking, heartwarming, funny and grim, Mark Smukler’s feature adaptation of his short film, Wildflower is a fascinating glimpse into corners of life film usually leaves untouched. Filled with unspoken warmth, spoken pain and a recognition of the difficulties of simple life, Wildflower upends the expected responsibilities of parents and kids with grace and rarely turning its characters into cartoons. When it diverges from its themes of family and parenthood Smukler and co-writer Jana Savage lose their way a bit, but none of that can cover up the heart that is frequently on offer.

Most of that heart belongs to Bea (Shipka), a teen with far too much responsibility on her hands trying to push off becoming an adult as long as she can. Not because she wants to but because she has to. With two neurodivergent parents at home, Bea is left performing the parental roles they can’t – working to pay rent, making sure everyone takes their medication, has a meal waiting for them, gets off to where they need to go on time. It’s a lot to put onto the shoulders of a teenager still trying to work out their own identity and desires for the future; cracks are begging to be formed. When she turns up in a coma at the hospital her friends and family gather to piece together what could have driven her to extremes.

It all sounds potentially twee and dire – a bad comedy sketch version of a Ken Loach film – but in Smukler’s hands Wildflower is both warm and bracing and far funnier than you might expect. Much of that is down its stellar supporting cast, literally jumping in from the get-go with grandparents Peg (Smart) and Loretta (Weaver) who tell us exactly who they are and why they’re hear with little more than a stare and snort. In a film about family you need a family and Smukler has given Bea a terrific one to bounce off of from her loving but handicapped parents (Mihok and Hyde) to her screechy grandparents and her overly yuppified aunt (Daddario), everyone is not only immediately real but immediately inviting. They dare you to look away from what they’re doing, even when it’s just a dinner conversation.

The downside to that is, when you surround your lead with eccentric characters with big personalities, they risk either being buried or dragged along behind unless they have some equal amount of charm. No one remembers anything about Zeppo except that he wasn’t one of the other Marx brothers. The straight man has an important job but it’s difficult to re-orient the heart of the narrative to them after bigger and better things have been unveiled. Hopefully that means the core is interesting enough to carry everything around on its own; more often it means the scene stealers get pushed to the edge and like a gravity well drag all interest along with them.

Wildflower does not have entirely that kind of trouble; Shipka is too strong with this kind of material to get lost in it. Even at her self-centered worst Bea remains relatable and mostly understandable, only occasionally falling victim to characterization by plot necessity. What problems it does have, along with much of its strength, are tied up in the flashback structure. As the family struggles to rationalize the Bea they think they know with the one in a coma full of drugs and alcohol Wildflower moves further and further back in time to create context for everything that comes after. After her parents meet almost by accident they quickly bring Bea into the world and decide it is time to move out of their family homes despite the fears and concerns of their own parents about how they will raise a child. Concerns that are not entirely unrealistic as Sharon has difficulty paying attention for long periods and is easily talked into buying alcohol for minors while Derek tries to have his 10-year-old daughter take on the family driving.

As deceptively manipulative as the opening vignettes could have been, they sing with life and reality. Sharon’s parents arguing about whether they are glad or not she is leaving home is as bracing and heart rending as anything on screen this year: Smart and Brad Garrett make every moment of their short screen time count. When young Bea almost kills herself in a car crash she begins living with her aunt (Daddario), a hilariously overdone helicopter mother who only exists as a counter point to Sharon but still manages to a sense of reality in her care for her sister and niece.

All that strength comes with a downside, however. As the flashbacks close in on the present day – now teenage Bea attending a private school and teenage life she tries desperately to keep separate from her family – the story morphs from the trials her family life and how it works despite itself to a more conventional coming-of-age story that cannot stand against what has come before. Derek and Sharon are unique, Peg and Loretta are unique, Joy and Ben are stereotypes but self-aware ones. Compared to them, Bea frequently comes across like a refugee from a 1990s Kevin Williamson film; it takes all Shipka’s strengths to find something real inside of her.

None of that invalidates what has come before, but it does weaken the whole. Some of that is the decision to hide what put her into the hospital as long as possible, which then requires a lot of plot manipulation and arbitrary character choices to get the decided point. Worse, the high school antics – none of which are unique or notably different than any random teen soap opera – push family to the side lines to give Bea the freedom to develop self-awareness. That leaves her trailing her already defined co-stars, and it’s a gap that’s never made up.

The warmth and humanity remain, however. And even if Wildflowers falters some in the landing the journey is still worth it.

7/10. Starring Kiernan Shipka, Dash Mihok, Charlie Plummer, Jean Smart, Alexandra Daddario, Kannon Omachi, Brad Garrett, Samantha Hyde and Jacki Weaver. Directed by Mar Smukler.

Mafia Mamma