Argylle

Outsized, overdone and ill-conceived, Argylle takes what could have been a fun concept about mistaken identity amid hidden identity into a convoluted mess which consistently undercuts itself.

Outsized, overdone and ill-conceived, Argylle takes what could have been a fun concept about mistaken identity amid hidden identity into a convoluted mess which consistently undercuts itself. Is it a lighthearted spy film about James Bondian super-agent? A meta-fiction comedy about real life and fantasy becoming mixed together? An action fable about both? Yes, no, all of the above, none of the above … no one can decide or seems to want to decide leaving nothing but an incoherent blob which stays far past its welcome and can’t even make up its mind about an ending.

The beginning is pretty solid. Not the star-studded action set piece it wants everyone to think the story is, but the introduction to best-selling novelist Elly Conway (Howard), creator of the ubiquitous Agent Argylle. Despite being a notorious agoraphobe who never flies or travels without her cat, Alfie, and an overbearing, nit-picking mother (O’Hara) she has nourished a global fanbase waiting breathlessly for her next spy epic. When some of those fans turn out to be real spies willing to kidnap Elly to discover the plot of her next novel which seem to predict real world events with great accuracy. Her only hope against the sudden terrors she has spent her life protecting herself from is rambling, eccentric former agent Aidan (Rockwell) who needs what she knows as well.

And if it just stopped there that would be fine. Howard and Rockwell have strong chemistry and real comedic rapport. When nefarious agents of the Directorate attempt to abduct Elly from a train, Aidan’s sudden rescue attempt becomes a ragtag ballet of misunderstanding, bullets and screams. The more confusing the situation gets, and the more Elly attempts to escape, the better Argylle is. If it stayed that way throughout, slowly seeking out clues amid confusion and repartee, that would be enough. But no one knows to leave well enough alone.

No sooner has Elly escaped one confusing situation than she finds herself in the middle of more double crosses, rescued by her own meddling parents (creating the brilliant paring of Cranston and O’Hara) and intermittently hallucinating her own creation (Cavill) trying to give her advice how to survive her increasingly dire situation. It’s all a hat on top of a hat on top of a hat. Vaughn seems to have no faith in how long any situation can keep his audience’s attention, preferring instead to keep whipping the story around into new directions and then doing so again just as we’re getting used to the new status quo. It’s all built on the idea of reveal rather than revelation and forgets the law of diminishing returns.

The idea of Howard in an action-comedy gunning down evil doers is a good one, but it’s so covered in meaningless twists and turns it loses its power and becomes a chore. Eventually one that won’t end as ever more secrets are added on, even to the last moment. No one seems to know what it should be so everything is thrown at the wall desperately hoping for the final form to spontaneously manifest itself. It’s a waste of its main characters, it’s a waste of its imaginary characters and ultimately it’s a waste of our time.

5 out of 10. Starring Bryce Dallas Howard, Sam Rockwell, Bryan Cranston, Catherine O’Hara and Henry Cavill.

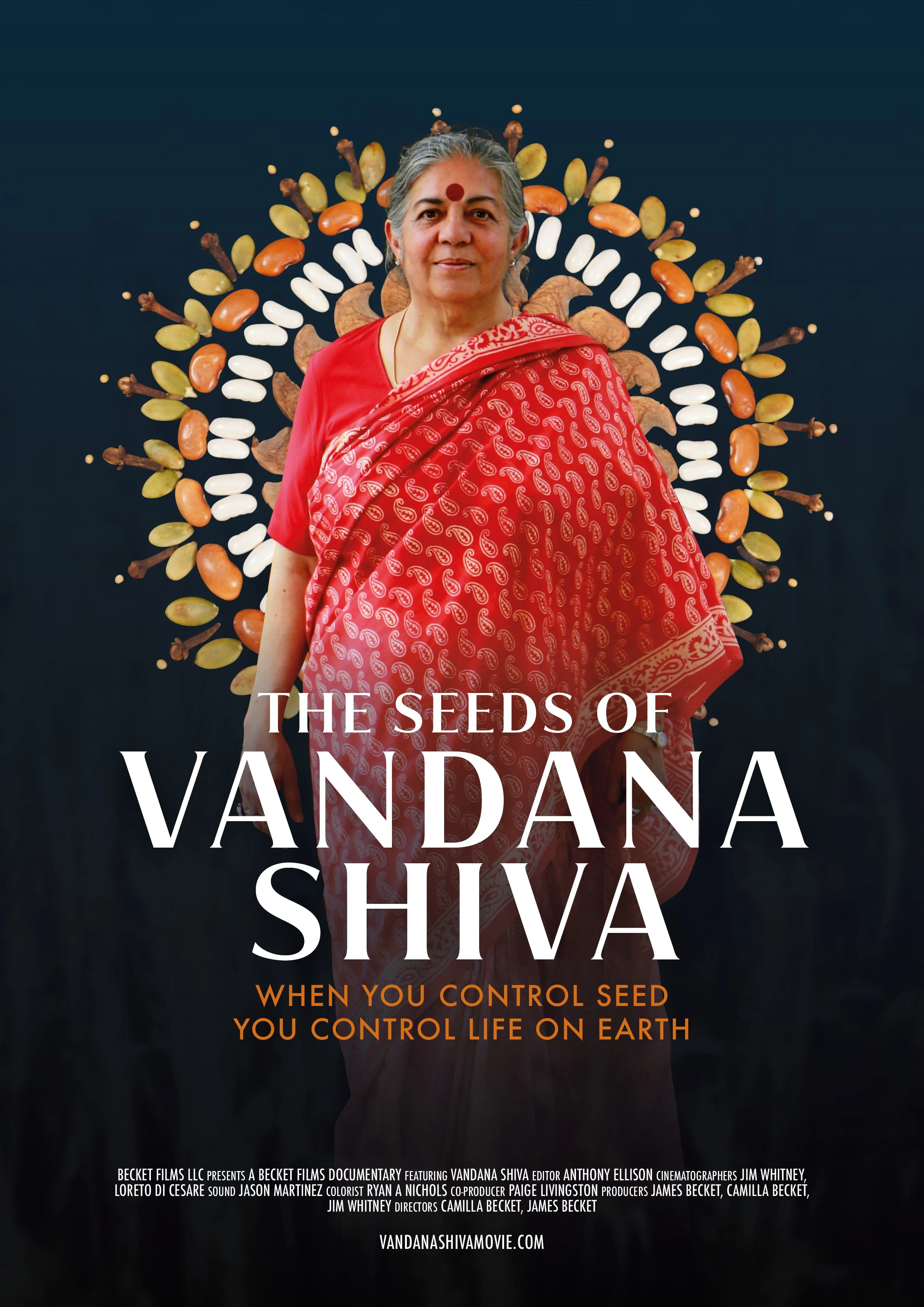

The Seeds of Vandana Shiva

Alternately insightful and off-its-rocker, wrestling with grand themes of colonialism, corporate greed and the roots of knowledge, Camilla and James Becket’s The Seeds of Vandana Shiva is ultimately interested in the complex question “can you be right about something even if you don’t know what you are talking about?”

Alternately insightful and off-its-rocker, wrestling with grand themes of colonialism, corporate greed and the roots of knowledge, Camilla and James Becket’s The Seeds of Vandana Shiva is ultimately interested in the complex question “can you be right about something even if you don’t know what you are talking about?” It’s not at all clear that’s the question the Becket’s know they are asking or even that it’s an issue at all, but it is at the heart of not just their film but the complexities of Vandana Shiva’s life and work, and the massive pushback she faces as she stares down global corporate forces.

An intellectual and activist, Shiva is a self-professed cross discipline didact trapsing across the fields of philosophy, physics and biology in a search for the connective tissue of all life. In the process she has run directly into the primary, extinction level crises facing mankind in the near future – climate change and food scarcity – and run them back to at least one primary root cause: corporate controlled, genetically modified food.

Across 20 years of activism, Shiva has opened a new front against global food control and particularly against agri-giant Monsanto which has won a number of high profile patent cases affirming that it owns its genetically engineered seed and whatever is grown from its seed (intentionally or not) while simultaneously using its corporate might and monopoly pricing power to force more and more of the worlds farmers to use said product. “It’s the East India Company, again,” a tribal elder tells Shiva as she tries to wake rural India to the danger creeping up on them and they are right. What government colonialism wasn’t able to achieve through centuries of war and plunder, corporate colonialism might just take with a few dollars, she warns.

It’s a piercing insight that others have made but not always with the perspicacity of Shiva, focusing as she does on agriculture companies that may not have the profile of Big Tech or Big Oil but are in many ways more fundamental to the changes currently happening on the planet, especially around soil erosion.

It’s also obscured by some of her other claims around what genetically modified food can and would do to the populace and its place in global climate change, which range from the interesting to the outlandish. Claims that she refutes less through pointed peer review and analysis and more by general explanation of her holistic study of the world and the way all of its structures are interwoven in a manner not all can perceive, as if she were the second coming of Carlos Castaneda. It’s an interesting point of view and picture of a strong-minded figure in the scientific and political world, one who for good or bad insists on taking on her opponents on her own terms.

The Seeds of Vandana Shiva does not take a particularly critical view to its subject’s claims, casting much of it as big agriculture opposition research designed to discredit a strident opponent and critique of their businesses. (Which it certainly is but that doesn’t make it false.). However, the Beckets are open enough in their coverage of her own claims and basis of belief – maybe because they believe, maybe not – to allow the viewer a deep view of Shiva and what she stands for and then make up their own minds. Many documentaries have never done so much.

7 out of 10

Directed by Camilla Denton Becket and James Becket

To Kill a Tiger

Late at night in the rural Indian village of Bero a young woman known as Kiran (not her real name) and her father Ranjit separately and together experienced one of the worst events that can befall a family when Kiran is accosted by several village locals and violently raped. It’s a reality which, as director Nisha Pahuja states at the beginning of To Kill a Tiger, is committed 10,000 times per year in India; an epidemic of sexual assault the country’s national and regional governments have been at a singular loss to affect in the face of local and systemic apathy.

Late at night in the rural Indian village of Bero a young woman known as Kiran (not her real name) and her father Ranjit separately and together experienced one of the worst events that can befall a family when Kiran is accosted by several village locals and violently raped. It’s a reality which, as director Nisha Pahuja states at the beginning of To Kill a Tiger, is committed 10,000 times per year in India; an epidemic of sexual assault the country’s national and regional governments have been at a singular loss to affect in the face of local and systemic apathy.

It’s one thing to see that calmly and directly written on a screen; it’s something else to see it play out in grueling reality over the course of years as justice is sought. Rather than try to move on and forget the assault Ranjit and his wife go directly to the authorities seeking justice, and quickly learning how great the obstacles to that are. Though the three perpetrators are easily discovered and arrested, no one in authority or even in the community is interested in what justice would require. Instead, Ranjit is pushed to marry his daughter to one of her assailants in order to reconfigure the attack as a marital dispute. Worse than Ranjit’s very logical cry “why would she want to marry someone who has assaulted her?” is the deafening silence which follows as the local government ministers clearly have no idea how to approach the problem beyond ‘get rid of it.’

Refusing to take the easy way out Ranjit pushes forward in a quest for justice. What he finds is incompetence and apathy in a staggering degree with a local government which falls back into byzantine rules (Ranjit can’t bring a case himself, a specific magistrate must do it and do it in specific hours on specific days, etc.) to insulate itself from what it and the populace around it see as an uncomfortable nuisance. The perpetrators themselves recognize the reality they are in, feeling emboldened enough to threaten those watching, as if their acquittal were a foregone conclusion.

In the face of this Ranjit and Kiran’s only choices are to quit and continue forward. As much as Tiger is focused on the systemic rot that makes such actions possible it is also a low key portrait in courage particularly of Ranjit as he presses forward with his case despite the stress, the wish that it wasn’t happening and a growing drinking problem. It is real courage, not the performed version of drama because it is without heroism recognizing it is not needed. All that is needed the will to continue on even as his long time friends and neighbors, and the government itself, try to just make everything go away.

As the village increasingly turns against Ranjit and his quest, demanding that he think of the villages reputation first and how people are talking about them because of the trial, unfortunate commonality with the worst of humanity raises its head. Similar to Ophul’s Hotel Terminus and its discovery of how many local French were perfectly happy to let Nazi collaborators return to their lives because “it was so long ago” and “why dredge up old memories,” the main goal of the everyday people is to put everything behind them and forget about it, not realizing that in their zeal to do that they are committing a sin almost as vile as the initial crime.

Similar to Ophuls, the filmmakers find themselves sucked into their own film as the populace also turns on them for daring to shine a light on Kiran’s plight, blaming those making noise (rather than the rapists themselves) for causing so much trouble to the point that filmmakers themselves must decide whether to go on and even offer cover to Ranjit before his final confrontation with the judge.

To Kill a Tiger is an intense, damning portrait of both society which supports violence and the gentile realistic bravery needed to combat it. A must see.

9 out of 10.

Directed by Nisha Pahuja.

Apolonia, Apolonia

What makes an artist? Not just the desire to create but the desire to do so above all else, the will to follow that impulse through and the luck to succeed. A lot of biopics have attempted to answer that question, usually by reciting the defining elements of their lives in an orderly progression of events, perhaps with some dramatics focused on at certain specific moments in time. They usually come to few if any answers because people are more than just the events that happened to them. Director Lea Glob was gifted with the opportunity to follow the life of an esteemed artist in the making, to watch them create themselves in real time over years and realize that she is asking it of herself (and the price to be paid for it), as well.

What makes an artist? Not just the desire to create but the desire to do so above all else, the will to follow that impulse through and the luck to succeed. A lot of biopics have attempted to answer that question, usually by reciting the defining elements of their lives in an orderly progression of events, perhaps with some dramatics focused on at certain specific moments in time. They usually come to few if any answers because people are more than just the events that happened to them. Director Lea Glob was gifted with the opportunity to follow the life of an esteemed artist in the making, to watch them create themselves in real time over years and realize that she is asking it of herself (and the price to be paid for it), as well.

Over the last 10 years Apolonia Sokol has carved out a niche for herself as one of the foremost new contemporary painters, focusing on figurative studies (frequently but not always women) in ambiguous moods and locations hinting at the depth of life in individuals beyond the single moments in time her canvases capture. Before that happened, however she was a struggling artist moving from city to city and gallery to gallery trying to find out what these figures mean to herself or to anyone else and if she even has something to say. And before that she was an intelligent young woman with a unique background, growing up in a small theater in Paris owned by her parents where she seemed destined to live a life in the arts. Was it because of her bohemian parents, because of the nomadic existence she lives after the her parent’s divorce, something deep inside of her from before birth, or none of those things?

Glob’s film knows better than to make any definitive statements but we can make some inferences. Sokol’s own parents, beyond putting her in the midst of creation as avocation from her youngest age also filmed much of her early life (including her conception and birth) to show back to her as an adult an give her a view on where she came from in a raw manner most wouldn’t. It opens a world to Glob, of Sokol as a young woman questioning what she wants out of life even as the foundation of her childhood is removed forcing her and her mother to relocate to Denmark. As an art student she is no different than any other 20 year old, primarily concerned with externalities like what will happen with her home, what will happen with her friend Oksana – a Ukranian ex-pat fighting against Russian aggression years before the actual invasion – and will she pass her exams.

Years later, having begun to navigate the fickle art world and its need of patronage to continue, she has become more than a subject for Glob. She is almost an anti-thesis, a woman who has turned her back on sort of domestic life – giving up any thought on children or family – to apply herself entirely into figuring out her creative self and how to make it work as a career and a life. Glob by comparison works with her husband and compares the difficulties of making that life work (including a very difficult birth that makes future children impossible) almost as a condemnation of Sokol has chosen to give up versus what Glob is forced to.

And yet she also clearly sees much of herself in Sokol as well as each focuses on portraits of women in an attempt to understand theme and the world. Gradually Glob finds herself drawn more and more into Sokol’s orbit like a real-life Persona, having conversations while Sokol bathes and even at one point training her own camera on herself while left alone in Sokol’s apartment. Is she making her film because Sokol herself is such an interesting person (yes) or is it to understand herself and the choices she has made in her life (also yes)?

Gradually, as real life always does, people move on. Sokol moves continually around the world, unmoored from life around her, following her muse wherever it takes her including fellowships and awards, as the the things which were once of paramount importance in her life fall away and are forgotten, suggesting perhaps they were not what made her such an interesting artist in the first place. Does Apolonia, Apolnia ever really answer its own questions? No, but not because it can’t, but because it realizes at the end that there is no answer.

8 out of 10.

Apolonia Sokol, Hervé Breuil, Lea Glob, Oksana Shachko and Alexandra Tlolka. Directed by Lea Glob.

The Beekeeper

To be or not to be,” a fluorescent coated, bottle blonde South African mercenary spits at the Jason Statham’s master beekeeper / special forces commando during their final confrontation. That mélange of ideas smashed into your face is all you need to know about David Ayer’s newest action film The Beekeeper or why you should see it. The only thing that could be better, and I hope it is true, is if each infinitive was actually spelled ‘bee’ in the script. (I’m just going to assume that it is and give it another point for audacity). That is the level of silliness at work and it really deserves to be seen to be believed.

“To be or not to be,” a fluorescent coated, bottle blonde South African mercenary spits at the Jason Statham’s master beekeeper / special forces commando during their final confrontation. That mélange of ideas smashed into your face is all you need to know about David Ayer’s newest action film The Beekeeper or why you should see it. The only thing that could be better, and I hope it is true, is if each infinitive was actually spelled ‘bee’ in the script. (I’m just going to assume that it is and give it another point for audacity). That is the level of silliness at work and it really deserves to be seen to be believed.

A revenge action thriller at heart no different than any other, Beekeeper posits a world filled with terrible people who view their fellow man as resources to be farmed like wheat or carp, and the only way to deal with such people is by force because legal and political systems can’t or won’t do it. Or at least they won’t do it in the thoroughly cathartic manner of hooking the worst person you know to a truck and driving him off a bridge at full speed. Even the government has accepted this reality, creating a group of ‘Beekeepers’ literally above the law whose job is to freelance identify and remove threats to the polity in the most direct manner possible. There is, as there has been with all of these since Death Wish, a troubling border shared with nihilistic fascism where might is the only thing that truly makes right and the only hope is that the ubermensch believes in morals and justice at some level.

Said superman here is, as he should always be, Statham: a former member of the secret Beekeepers who has retired to keep bees because (and this is true of everything in The Beekeeper) the metaphor he lives by is both figurative AND literal. There is no distinction between metaphor and reality, and if for one moment it seems like there might be Ayer and screenwriter Kurt Wimmer will blow it up. When the widower (Rashad) he is renting beekeeping space from loses her life savings in an internet scam Statham takes it upon himself to find the perpetrator and burn their business to the ground as well as anyone connected to it. Uncovering an increasing web of perpetrators leading up to the White House itself, and remembering the beekeepers maxim to run out damaged bees that endanger the hive, Statham takes the bees instinct as his own even if it means killing the President. And in between, many facts about bees are recited. If it turned out the script was 20 pages light and the filmmakers filled it in with excerpts from the Wikipedia page on bees, I would believe it.

Yes, it’s stupid. That’s a good deal of its charm. Considering how much of the film is bathed in neon and over the top nonsense it’s not a large leap to expect the filmmakers know it, too. When Statham finally finds the scammers they are not put upon keyboard warriors stacked in endless rows of cubicles but work in an a neon painted boiler room with club lights and EDM blaring over the speakers while an obnoxious crypto bro yells at them over a megaphone to steal harder. The villains are like reverse huntsman, painted in the brightest, broadest colors possible (the more neon the better) to make sure they easily identified. So when a fellow Beekeeper shows up to put Statham out to pasture and she walks around on stiletto heels with a purple mohawk and a minigun in the back of her truck the only response can be “sure, why not.”

It doesn’t make much sense, with only the smatterings of connective tissue and human beings who cannot react like any sort of human being or even notice how weird everyone around them is behaving. Recognizing the defects and the futility of trying to fix them, Ayer fills his screens with gifted actors who can ramble on nonsense with the best of them so that they can talk a lot about bees. If it was a bet to see how many times Jeremy Irons can be made to say the word ‘bee’ … then it was time well spent. The only one left on the outs is an insouciant Josh Hutcherson as the most entitled, ridiculous of crypt bros whose only job is to be imminently punchable but is not in the least believable as a villain.

Is it all really, really stupid? Yes. It is gloriously, wonderfully, joyously stupid. It may be the dumbest thing made this year. Everyone should see it immediately.

4 out of 10 (but really 8 out of 10)

Starring Jason Statham, Emmy Raver-Lampman, Josh Hutcherson, Jeremy Irons, Jemma Redgrave, Bobby Naderi, David Witts, Megan Le, Taylor James, Minnie Driver and Phylicia Rashad. Directed by David Ayer.

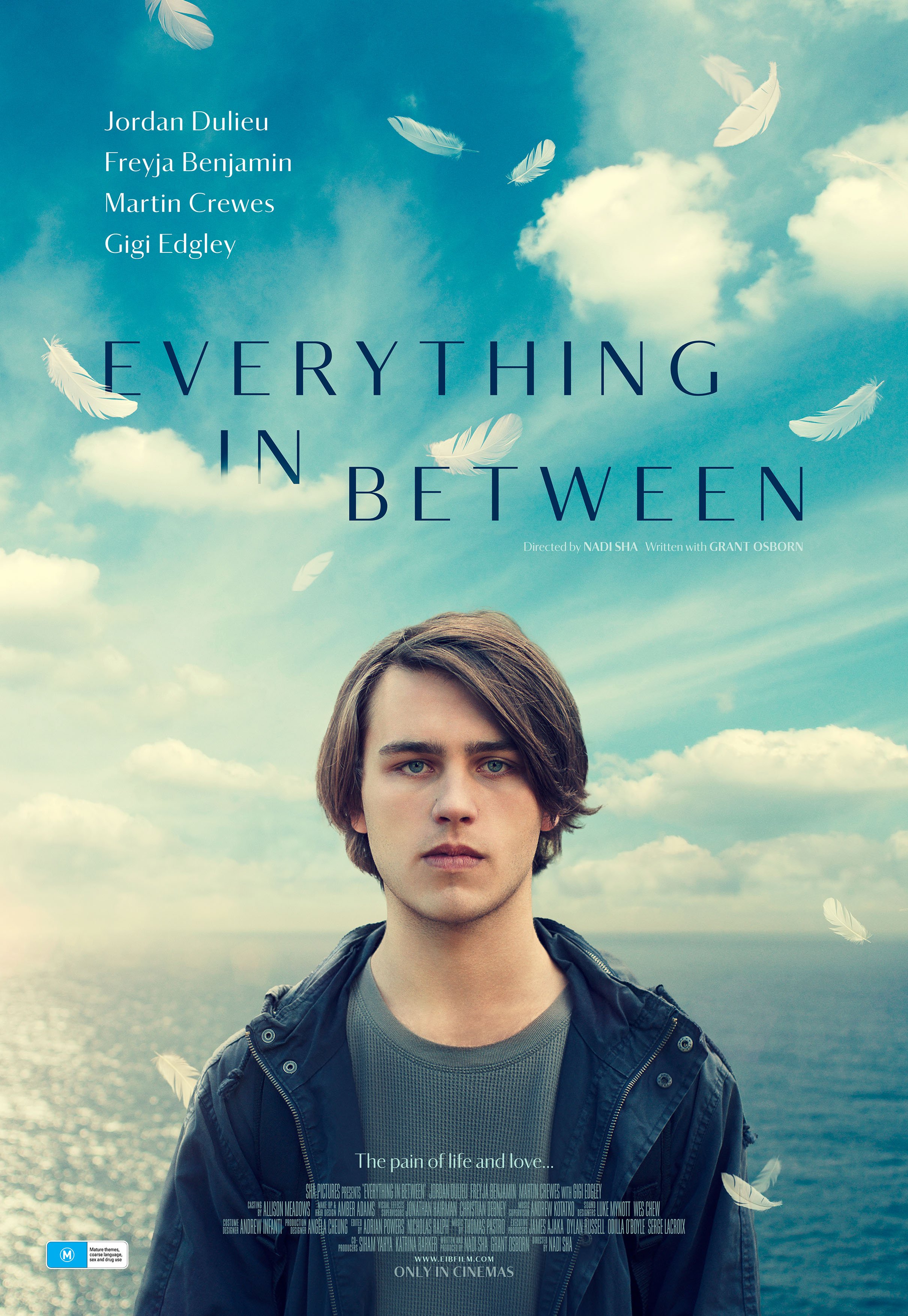

Everything in Between

Physicists tell us the world is mostly empty. What we perceive of as solid and real are in fact motes of being separated by vast distances between which the entirety of reality can pass without notice. And yet those burning singularities invariably become entangled, creating matter and form and the presence of a physical world. We're a compact of contrasts, both solid and empty, real and illusory. Nadi Sha's Everything in Between is a similar study -- sentimental but philosophical, thinly sketched but deeply complex, narrowly focused but uniquely universal.

Physicists tell us the world is mostly empty. What we perceive of as solid and real are in fact motes of being separated by vast distances between which the entirety of reality can pass without notice. And yet those burning singularities invariably become entangled, creating matter and form and the presence of a physical world. We're a compact of contrasts, both solid and empty, real and illusory. Nadi Sha's Everything in Between is a similar study -- sentimental but philosophical, thinly sketched but deeply complex, narrowly focused but uniquely universal.

It would be easy to think there's not much else to say about middle class ennui; it's been focus of western literature since the middle class evolved and of independent film since at least the 70s. David Knight (Jordan Dulieu) could be an escapee from any one of them, an introverted and lonely scion of comfortable but oblivious parents (Gigi Edgley and Martin Crewes) feeling isolated from the world around him, adrift in that infinite void between us. When an aborted suicide attempt lands him in the hospital he finds himself sharing space with the unmoored, untroubled Elizabeth (Freyja Benjamin) who takes life as it comes until she starts suffering from the symptoms of a strange disease.

On the outside Everything in Between sits too comfortably in the orbit of other, similar films that trod this similar ground. David, his primary needs covered his entire life and his parents oblivious to his need for purpose and inability to self-create it, and Elizabeth, a free spirit with a general, genial spirituality and little use or experience with the practicality of life, are primary constructs of the genre. Sometimes the bonding element is tragedy, sometimes it is comedy, sometimes it is the purely mundane. Everything in Between camouflage itself in those tropes before throwing its nighted colors off to expand its focus and try something new.

As Elizabeth's disease expands, David brings her home (she has nowhere else to) and into the path of his parents who are still dealing with the trauma of being pulled from their personal concerns, the opportunity for easy bathos expands but writer-director Sha easily squashes it. Instead, forced into close proximity and the gap between them diminished, what could have been flimsy sketches of characters expand to reveal inner lives. Elizabeth ignores the easy cloak of the manic pixie dream girl to reveal a frightened woman facing mortality at a young age and in no mood to become someone's fixation. Martin, a self-involved financier who hoped to brush off his son's suicide attempt finds himself offering up the support David has needed without entirely realizing it, while mother Meredith bristles at someone else taking over a role of importance in David's life and slowly realizes where she herself has pushed him away. As philosophical think piece on existence, Everything trends towards empty pop psychology but as interpersonal character drama it soars. The worse things get, the better Everything becomes.

It's a study in contrasts all the way down; waifer thin characters but deep and affecting performances (particularly from Benjamin and Dulieu), light thematic depth but complex family dynamics, straightforward scripting but confident and assured direction. Rather than getting lost within the great forest of independent bourgeois critique, Everything in Between stands on its own like a lighthouse saying something more, and better, about modern life.

Starring Jordan Dulieu, Freyja Benjamin, Martin Crewes and Gigi Edgley. Directed by Nadi Sha.

JazzTown

What is jazz? It’s difficult to say about any artform and more so about one born of improvisation and spontaneity. The very difficulty in defining it also makes it almost impossible to make any firm predictions on where it is going, how it will change into the future. That doesn’t stop director Ben Makinen from trying in JazzTown, his paean to the jazz scene of Colorado, but like the artform itself the answers he finds are frustrating and uncomfortable by design.

What is jazz? It’s difficult to say about any artform and more so about one born of improvisation and spontaneity. The very difficulty in defining it also makes it almost impossible to make any firm predictions on where it is going, how it will change into the future. That doesn’t stop director Ben Makinen from trying in JazzTown, his paean to the jazz scene of Colorado, but like the artform itself the answers he finds are frustrating and uncomfortable by design.

Part of that is because, as many of the musicians Makinen interviews explain, jazz is always evolving in a way few musical styles do. Whatever it started as, it is not that way now and whatever it is now, it will not be tomorrow. That uncertainty and surprise is part of what makes jazz what it is, not least because there’s no telling where it will emerge. Colorado in general, and Denver in particularly, are not generally thought off in the list of major jazz hubs, but in his several years chronicle of the local jazz scene there Makinen a culture and history as deep and intrinsic to the artfrom as anything from Chicago or Kansas City or New Orleans.

More importantly, and frequently with more sorrow, it’s a scene with a keen idea of where it sits in the jazz firmament and where the art form itself is likely going. Digging into the initial background of jazz in Colorado who is playing it there, JazzTown on its surface just seems like a series of interesting but brief interviews with local musicians offering up anecdotes about their time around the city and how they fell into form to begin with. Each small story, however, builds to a more interesting whole, creating a mosaic that when viewed from a distance defines and shapes the history of the town and offers a view on it (and its music) quite different from the standard expectation. In many cases artists just fell into it due to the draw of the rhythm and soon found themselves ensconced a life they may not have expected.

None of them, however, have any illusions about how that has been rewarded or what it means for those coming after them. More than one old hand takes the moment of the film to let whoever comes after know that it wasn’t worth it and to find something else to do with their lives. It quickly becomes a sad and depressing picture of cultural gentrification, one where the reality that there’s no way to make a living doing it leaves it only to future practitioners who don’t have to worry about making a living at it. The foresee a world where jazz is no longer created for casual audiences who stumble upon it as they had in the past, but something created only by a select group of musicians for a select group of musicians, an ouroboros continually feeding on itself.

Within that misery there are still seeds of hope. Makinen takes some time to focus on the next generation of musicians coming up, fully aware of where the form came from and how it has changed. A young drummer, not yet worrying about how to make money doing it, focuses more on how the sound has changed in reaction to other musical forms around it and reminding at the end of the day that it’s the sound that is heart of the form. As long as that still exists, in some form, jazz will never die.

The Country Club

The rich, they’re just like us except for their views on relative effort, merit, societal norms or achievement. With no outside desires driving them on their world revolves around keeping up their existing parasocial relationships (because in a world where everything is fake every relationship is parasocial) and maintaining appearances. The only thing they are good for externally is to provide resources to the hard working up-and-comers who are trying to achieve … in order to become just like them.

The rich, they’re just like us except for their views on relative effort, merit, societal norms or achievement. With no outside desires driving them on their world revolves around keeping up their existing parasocial relationships (because in a world where everything is fake every relationship is parasocial) and maintaining appearances. The only thing they are good for externally is to provide resources to the hard working up-and-comers who are trying to achieve … in order to become just like them. It’s a dynamic ripe for satire and if there is a failing to Fiona and Sophia Robert’s sly take down of country club culture it’s that it’s not weird enough.

The sisters Robert here are the sisters Cartwright, a pair of ambitious teens with great ambitions for what they want out of life but few resources to make it happen. The answer to their problems arrives in the form of a letter mistakenly sent to Elsa (Sophia Robert) who happens to share a name with the influencer daughter of a Connecticut blue blood family. Invited to a junior golf tournament, aspiring player Sophia sees a chance to win enough money for college while Tina (Fiona Robert) sees the opportunity to acquire investors to support her as a fashion designer. What they find is beyond their wildest imaginings, a world of petulance and expectation embodied in the beret wearing weirdness of Roger Kowalski (Higgins), a lost little boy who only cares about winning the tournament but doesn’t particularly care about playing in it.

A sly and witty screenplay by the Robert sisters is the engine that powers The Country Club, filled with small but perfectly placed side characters engendering just the right amount of weirdness. Like Caddshack and other class warfare comedies before it, the dynamic between the put upon club workers and their insouciant employers is its core. It’s a little constrained by a smaller budget and cast, putting most of that onto the shoulders of beleaguered Lumer (Ormond), Roger’s caddy and only friend who tries to satisfy is every whim even if it means playing for him during the tournament. It’s a lot to put on one character’s shoulders, alongside becoming the focus of Tina’s romantic attentions and he can’t quite carry it all but he also doesn’t need to. The Country Club wisely moves along to one of its more fanciful supporting characters to keep its more conventional aspects from dragging things down.

Director Fiona Robert shows a keen eye for filling those roles, from James Urbaniak’s sleezy club manager (who we could sadly use much more of) who loves nothing more than tormenting his assistant, to Magaret Ladd’s elder grand dame of the tournament or Elaine Hendrix as the domineering mother who answers many questions about why Roger is the way he is. Everything speeds along at a tidy 89 minutes which doesn’t give most characters more than exactly what the plot needs of them, but nor do they need it. Do we need to spend more than a single outing with chatty, self-involved Mary-Anne Montreal (Chow) or the handsome and self-involved Marshall (Levi) to get what we need from them? Not really. Familiarity really does breed contempt; any more time with any of them would have ruined the joke and increased the dullness.

In no one is that more obvious than Roger himself. Funny in small doses, Higgins’ pampered momma’s boy is less and less funny and more and more irritating the longer he is on screen. Not least because pulls attention away from the more interesting Cartwright sisters and offers little of interest in return as he slowly swallows the film whole. A cardinal warning of the old saying about less being more, Roger nearly derails everything interesting in The Country Club. It's not enough to hide the promise of future comedy outings from the Robert’s, just a hope that they leave buffoons in the background next time.

Starring Sophia Robert, Fiona Robert, John Higgins, Sean Ormond and James Urbaniak. Directed by Fiona Robert.

Discontinued

Alternately bleak and hopeful, Trevor Peckham’s Discontinued is a refreshingly original sci-fi take on addiction, maturity and the connective tissue of society that refuses to baby its audience even when it probably should.

Alternately bleak and hopeful, Trevor Peckham’s Discontinued is a refreshingly original sci-fi take on addiction, maturity and the connective tissue of society that refuses to baby its audience even when it probably should.

Picking apart the why’s and needs for society to exist, Peckham’s necessarily small mindbender plays with big ideas cunningly concealed within the clichés of other genres. Disaffected twentysomething Sarah (Hutchinson) could be mistaken for an escape from another, lesser comedy about a burgeoning adult who pushes society away because they are terrified of joining it. A lot of them have been made. All of that is pushed out the window, so to speak, when a charismatic hologram (Fishburne) appears on televisions worldwide to let everyone know the world doesn’t actually exist, it’s merely a computer simulation which will soon end. Everyone in the world, from Sarah to her parents to her therapist (Picardo) have to decide if they will be removed from the simulation and inserted into a permanent heaven where they will experience the most blissful moments of their lives over and over, or if they will decide to remain behind in a largely empty world which will likely gradually fall apart.

There are a lot of directions a story can go from that direction, from questions of what do those types of questions mean to how people respond to such a change in all they know. Discontinued is not dark enough to delve into Solaris-like existentialism or comedic enough to highlight a discussed but unseen descent into debauchery as consequence is removed from life choices. Like the proverbial terrorist forcing a stark character choice via explosives, the decision here is so starkly keyed to Sarah’s own disassociation with the world around her it could have been specifically engineered for her. And maybe it was.

Alone among anyone she knows, Sarah earnestly questions whether deciding to remain behind in quiet isolation isn’t the superior choice. Like Will Freeman she believes every person really is an island and likes it that way. Or at least she thinks she does.

Buried deep, deep (maybe too deep) within this is the reality of Sarah’s past battles with alcoholism and the reality that if the world hadn’t ended she was headed towards relapse. She systematically ignores her therapist’s advice to stop worrying about what she can’t control. That is, to recognize her powerlessness in the face of addiction, let go of a need for control and trust in a higher power. In this case the higher power just happens to be an artificial intelligence enabling self-actualization for its subject but tomato, tomato.

If the consequences do remain small, they are still surprising. Refusing to be pinned down by the easy narrative structure Discontinued masquerades in at the start, Peckham continually twists the narrative into unexpected directions in order to wear down Sarah’s prickly exterior. Rather than fill the time with interactions among friends and family heading to the final goodbye, Discontinued suddenly jumps forward into the empty world Sarah was pondering and find it to be not at all bad. That only lasts long enough for the obvious flaw in her desire to make itself apparent before Peckham changes perspective again. Discontinued always keeps you on your toes.

The lack of scale works against some of the large ideas Peckham is playing with and puts a tremendous amount on Hutchinson’s shoulders but she carries it off even weighed down by some early indie film cliché that should have died already. It quickly burns itself down to its essence, however, revealing a thoughtful and bracing thought experiment about the need for human connection and the ways we try to convince ourself it’s not real.

Wildflower

Heartbreaking, heartwarming, funny and grim, Mark Smukler’s feature adaptation of his short film, Wildflower is a fascinating glimpse into corners of life film usually leaves untouched

Heartbreaking, heartwarming, funny and grim, Mark Smukler’s feature adaptation of his short film, Wildflower is a fascinating glimpse into corners of life film usually leaves untouched. Filled with unspoken warmth, spoken pain and a recognition of the difficulties of simple life, Wildflower upends the expected responsibilities of parents and kids with grace and rarely turning its characters into cartoons. When it diverges from its themes of family and parenthood Smukler and co-writer Jana Savage lose their way a bit, but none of that can cover up the heart that is frequently on offer.

Most of that heart belongs to Bea (Shipka), a teen with far too much responsibility on her hands trying to push off becoming an adult as long as she can. Not because she wants to but because she has to. With two neurodivergent parents at home, Bea is left performing the parental roles they can’t – working to pay rent, making sure everyone takes their medication, has a meal waiting for them, gets off to where they need to go on time. It’s a lot to put onto the shoulders of a teenager still trying to work out their own identity and desires for the future; cracks are begging to be formed. When she turns up in a coma at the hospital her friends and family gather to piece together what could have driven her to extremes.

It all sounds potentially twee and dire – a bad comedy sketch version of a Ken Loach film – but in Smukler’s hands Wildflower is both warm and bracing and far funnier than you might expect. Much of that is down its stellar supporting cast, literally jumping in from the get-go with grandparents Peg (Smart) and Loretta (Weaver) who tell us exactly who they are and why they’re hear with little more than a stare and snort. In a film about family you need a family and Smukler has given Bea a terrific one to bounce off of from her loving but handicapped parents (Mihok and Hyde) to her screechy grandparents and her overly yuppified aunt (Daddario), everyone is not only immediately real but immediately inviting. They dare you to look away from what they’re doing, even when it’s just a dinner conversation.

The downside to that is, when you surround your lead with eccentric characters with big personalities, they risk either being buried or dragged along behind unless they have some equal amount of charm. No one remembers anything about Zeppo except that he wasn’t one of the other Marx brothers. The straight man has an important job but it’s difficult to re-orient the heart of the narrative to them after bigger and better things have been unveiled. Hopefully that means the core is interesting enough to carry everything around on its own; more often it means the scene stealers get pushed to the edge and like a gravity well drag all interest along with them.

Wildflower does not have entirely that kind of trouble; Shipka is too strong with this kind of material to get lost in it. Even at her self-centered worst Bea remains relatable and mostly understandable, only occasionally falling victim to characterization by plot necessity. What problems it does have, along with much of its strength, are tied up in the flashback structure. As the family struggles to rationalize the Bea they think they know with the one in a coma full of drugs and alcohol Wildflower moves further and further back in time to create context for everything that comes after. After her parents meet almost by accident they quickly bring Bea into the world and decide it is time to move out of their family homes despite the fears and concerns of their own parents about how they will raise a child. Concerns that are not entirely unrealistic as Sharon has difficulty paying attention for long periods and is easily talked into buying alcohol for minors while Derek tries to have his 10-year-old daughter take on the family driving.

As deceptively manipulative as the opening vignettes could have been, they sing with life and reality. Sharon’s parents arguing about whether they are glad or not she is leaving home is as bracing and heart rending as anything on screen this year: Smart and Brad Garrett make every moment of their short screen time count. When young Bea almost kills herself in a car crash she begins living with her aunt (Daddario), a hilariously overdone helicopter mother who only exists as a counter point to Sharon but still manages to a sense of reality in her care for her sister and niece.

All that strength comes with a downside, however. As the flashbacks close in on the present day – now teenage Bea attending a private school and teenage life she tries desperately to keep separate from her family – the story morphs from the trials her family life and how it works despite itself to a more conventional coming-of-age story that cannot stand against what has come before. Derek and Sharon are unique, Peg and Loretta are unique, Joy and Ben are stereotypes but self-aware ones. Compared to them, Bea frequently comes across like a refugee from a 1990s Kevin Williamson film; it takes all Shipka’s strengths to find something real inside of her.

None of that invalidates what has come before, but it does weaken the whole. Some of that is the decision to hide what put her into the hospital as long as possible, which then requires a lot of plot manipulation and arbitrary character choices to get the decided point. Worse, the high school antics – none of which are unique or notably different than any random teen soap opera – push family to the side lines to give Bea the freedom to develop self-awareness. That leaves her trailing her already defined co-stars, and it’s a gap that’s never made up.

The warmth and humanity remain, however. And even if Wildflowers falters some in the landing the journey is still worth it.

7/10. Starring Kiernan Shipka, Dash Mihok, Charlie Plummer, Jean Smart, Alexandra Daddario, Kannon Omachi, Brad Garrett, Samantha Hyde and Jacki Weaver. Directed by Mar Smukler.

Mafia Mamma

Has any modern director fared worse after great studio success than Catherine Hardwicke? After crafting intricate grungy dramas like Thirteen and The Lords of Dogtown she launched the fantastically successful Twilight film series only to be exiled from her own creation even as it grew and grew. Since then she has chased similar heights in both fantasy horror (the magnificently bizarre Red Riding Hood) and character drama but has mostly fallen short from the successes of her early career. Muddled and unfunny, Mafia Mamma may be the nadir of her post-Twilight work.

Has any modern director fared worse after great studio success than Catherine Hardwicke? After crafting intricate grungy dramas like Thirteen and The Lords of Dogtown she launched the fantastically successful Twilight film series only to be exiled from her own creation even as it grew and grew. Since then she has chased similar heights in both fantasy horror (the magnificently bizarre Red Riding Hood) and character drama but has mostly fallen short from the successes of her early career. Muddled and unfunny, Mafia Mamma may be the nadir of her post-Twilight work.

There are fish out of water stories and there are fish into a gun fight stories and Kristin (Colette) is definitely living the latter. A cozy New York ad executive, Kristin returns to Italy for the first time since she was baby to attend her grandfather’s funeral only to discover he was not only a long-time mafia chieftain, but that he has left control of the family business to Kristin. With her professional and family life deteriorating in America, and the possibility of romance with a friendly local, she ignores all her common sense and sets about making peace with the other warring families. With a burgeoning new career and a new boyfriend it looks like Kristin may have finally found her purpose in life, at least until a rival families hitman shows up looking for her along with her ne’er-do-well husband and the police and suddenly she’s discovering why the mafia doesn’t have a retirement plan …

The fact that there have been so many ‘odd man sucked into the mafia’ films suggests there is a fair amount of juice in the idea. Analyze This, Mickey Blue Eyes – it was on the verge of becoming a sub-genre on its own back in the early 2000s. Which is, not coincidentally, the era it feels like Mafia Mamma has escaped from. Old jokes, old set ups, old punch lines – there doesn’t seem like much in it that hasn’t been tested and re-tested through many of the mediocre comedies that preceeded it. From Kristin’s early success leading the family to a disastrous date with an assassin or the return of her worthless ex, there is nothing in Mafia Mamma that feels the least bit surprising. And comedy without surprise is not comedy, it is nothing.

Collette does her best to elevate things, or at least to cover up the cracks with sheer manic energy but there is a lot to cover up. Only when Kristin and consigliere Bianca (Bellucci) open up about the difficulties of trying to succeed in a man’s world does Mafia Mamma seem to cultivate its own identity or come up with something to say. But those moments are few and fleeting, making way for more gags about Kristin’s attempt to balance her double life or explain to her teenage son that she’s become a mafia Don. For as much as she may push against the old way of doing things, Mafia Mamma is ensnared by them.

As interesting as it is to see Hardwicke trying comedy out, nothing and no one is getting elevated here. None of the keen eye for character from her early work or even the strength of casting and zeal for lunacy of her studio work comes through. Maybe if it had come out a few decades ago it would have been just another mafia comedy at least. Now it’s not even that.

4/10. Starring Toni Collette, Monica Bellucci, Tim Daish and Giuseppe Zeno. Directed by Catherine Hardwicke.

Showing Up

Adult relationships are hard, and the relationship with the self is hardest of all. It would be too much to say this is the core of all of Kelly Reichardt and Michelle Williams’ four collaborations together. Other films have been as much about the relationship with nature in a way Showing Up is not, but all of them ultimately return to the self and the need to understand it before being able to enter the world outside. There is no guarantee of success, or even of greater awareness of personal flaws, only that time will pass, and everyone will get a little older. The only real success is showing up at all.

Adult relationships are hard, and the relationship with the self is hardest of all. It would be too much to say this is the core of all of Kelly Reichardt and Michelle Williams’ four collaborations together. Other films have been as much about the relationship with nature in a way Showing Up is not, but all of them ultimately return to the self and the need to understand it before being able to enter the world outside. There is no guarantee of success, or even of greater awareness of personal flaws, only that time will pass, and everyone will get a little older. The only real success is showing up at all.

Portland artist Lizzie (Williams), for all her introspection, has not yet realized that. Preparing for a major, potentially career altering exhibit, all of her attention is focused inward leaving her oblivious to her fraying relationships with her friend/landlord (Chou), her mother, her eccentric neighbor (Benjamin). It’s not until life literally crashes into her in the form of a wounded bird Jo passive aggressively forces her to care for that the idea there is more to life than her personal neuroses even occur to Lizzie. Alternately pushing those close to her away and wondering why she is doing so; Lizzie tries to get herself ready for her show while facing for the first time the question of why she makes her art in the first place.

Ensconced back in the Portland suburbs, Showing Up has all Reichardt’s characteristic touches. The pacing is deliberately slow in a story that is focused on slow character revelation (and maybe change) rather than plot. The unexpected intrusion of nature on Lizzie’s life is symbolic arrival for the opportunity of grace if not change, an opportunity by no means guaranteed to be taken up on. Although returned to the present day from the wild valleys of First Cow, Reichardt’s last film, Showing Up is if anything wilder and further from civilization. Full of heavy silences expanding on the visual distance between characters that cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt keeps looking for, Reichardt’s typical slow examination of characters in their spaces is magnified even as the time is stretched.

On the one hand that provides plenty of opportunity for Williams to bounce off the world around her and show Lizzie’s subtle facets even as she seems to do very little. Even more introverted than her lone homesteader, Lizzie seems to be listening (but not hearing) the characters around her without ever interacting with them, but her face tells a different story. The small moments of emotion and reaction seeping in is some of the best acting of the year already and proof of Reichardt’s theory of minimalist filmmaking. It’s also something not every story can sustain; the further from nature she gets the more the stories seem to need. The film has become the wounded bird trapped in a cage, full a meaning inside of its small world but surrounded by an increasing wilderness.

None of that can hide that fact that Showing Up is as fascinating and intricate a character study as Reichardt and Williams have managed. It lacks the growing tension of Meek’s Cutoff or the poetic naturalism of First Cow, though not for lack of trying, but with patience and effort it does have its own pleasures to unveil. At some point it feels inevitable that we will reach the edge of too little but it’s not here yet. Until then Reichardt and Williams have once again delivered us something we can glory in.

7/10. Starring Michelle Williams, Hong Chau, Maryann Plunkett, John Magaro and André Benjamin. Directed by Kelly Reichardt.

Burt Reynolds’ Last Interview

One of the many frequent refrains and regrets of the modern franchise and nostalgia focused blockbuster era of Hollywood is the ‘death of the movie star.’

One of the many frequent refrains and regrets of the modern franchise and nostalgia focused blockbuster era of Hollywood is the ‘death of the movie star.’ The idea, often correct, that modern audiences respond less to specific talented and charismatic individuals and more to one or two specific characters they play or series they appear in. The days when a crowd was in love enough with an actor or actress to follow them from film to film across a range of genres and quality levels, a foundational element of the business, are gone. They’ll go see Top Gun and Mission: Impossible but that doesn’t guarantee they’ll watch other Tom Cruise movies. The movie star as a singular attraction is no more.

So the refrain goes. And for people coming into film in the current era, the idea of a movie star itself may seem archaic and hard to fathom. Sure there are a couple but most of the time it’s the movie itself, not the player. To those kinds of audiences it would be very difficult to explain just how important Burt Reynolds was from the late 70s to the early 80s. How could one individual mean so much as to a movie getting made or not because of him? It’s the totality of the experience that matters! Burt Reynolds: The Last Interview will not fully explain that, it is not looking to sum up the entirety of his place in the filmmaking schema, only to shine one last light on it. But for those who were there it is both one last reminder of what movie stars were and a last moment of insight and reflection from an icon just before his passing.

Filmed several months before Reynolds’ unexpected passing while preparing for a role in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, the interview was never intended to be Reynolds’ last word on his own career. Intended initially as a piece for director Rick Pamplin’s documentary on the difficulty in financing filmmaking, it quickly goes off into its own place as Reynolds’ expresses his disinterest in the original subject and instead becomes – intentionally or not – an artifact of the end of a specific era. In process is as scattershot as that sort of raw, unfocused questioning is; rather than use specific pieces as part of a larger focused narrative the way documentary normally does, Pamplin instead chooses to feature almost the entirety of the interview, aware of the importance of it as an item in and of itself.

Recognizing the issues with comprehension that creates, the rest of Last Interview is focused on providing some context to Reynolds’ threads, particularly around his focus on teaching acting and directing and desire to pass along to the next generations. It doesn’t create or deliver an overarching explanation of Reynolds in his time and place – viewers not already familiar with him may will not get an idea why he was important from this film alone – but it does shine a light on some of the lesser-known aspects of his life and career from his time as a benefactor theater in his home of Jupiter, Florida during the height of his fame to his return to it later in his life.

The life and times of the various Burt Reynolds’ theaters is the focus around which much of Last Interview focuses, from the current administrator of the community theater that once bore his name to his former manager who had helped him direct his energies. The remanences are all very specific to small but engaging anecdotes about his life, details around the edges that don’t give much information about the whole but have their own interest on their own. Ironically, or perhaps not, the most complete view of Reynolds’ in respect to his greater career comes from the man who would have been his last director, Quentin Tarantino.

Cast to play George Span, the owner of the Span Ranch (portrayed in the film by Bruce Dern), Reynolds had performed one full rehearsal of Hollywood with the full cast and was preparing to start filming when he passed away. In the middle of all of this, Tarantino with his typical recall ties both the last days of Reynolds preparing to recreate 1969 Hollywood with the actors own original breakthrough in 1969 Hollywood, in the process creating some idea of what Reynolds was for those who have never seen one of his films.

Burt Reynolds: The Last Interview is exactly what it says on the tin. It doesn’t provide enough context to fully explain who Reynolds was and only makes any real sense to those who already knew of him. But for that group it’s a fascinating glimpse into what has become an increasingly endangered species – the movie star.

Rating — 6.5 out of 10

Starring Burt Reynolds, Quentin Tarantino, C. Todd Vittum, Rick Pamplin, Andrew Kato, Chuck Elderd and Michelle Hillery

Fairways to Happiness

What is happiness? What does it mean in relation to everyday life, why do we search for it and how can we find it? Director Doug Morrione has decided to search for them in the first place you’d expect … a golf course.

What is happiness? What does it mean in relation to everyday life, why do we search for it and how can we find it? Director Doug Morrione has decided to search for them in the first place you’d expect … a golf course.

No it’s not a facile sports story or advertisement for a good walk ruined (though it is an ad for other things), so much as more complete metaphor for this particular part of the human experience than you might think. The golf course in question is country club in Dubai where ex-patriate Eugene Kerrigan challenges himself to score lower than 80 in a day’s shooting – the line between an amateur and a professional player. Why? Because it gives him something to strive towards and challenge himself with and in the process define his days and or provide a sense of accomplishment even if success can’t offer any tangible gain to the quality of his life. It is simultaneously immaterial and one of the most important ways he could spend his time.

Like most of the other subjects of Morrione’s documentary Kerrigan is one of the immigrant inhabitants who make up some 85% of Dubai’s population, brought in to build the nation’s infrastructure and businesses, provide services to the increasing influx of individuals doing that work or simply looking for the opportunity to build a new life. And in many cases being a spouse of someone doing that, coming along for the ride and trying to figure out ‘what to do now?’

Some of them start new hobbies, some of them do nothing but watch the grass grow, many start new businesses and in the process make sure everyone knows how easy that is in Dubai in pieces of the films occasional proselytizing. In between the semi-professional promotion there is more insightful introspection into why these individuals are doing what they are doing and what are they looking for? ‘How is happiness defined’ turns out to be as tricky a question as ‘how do we achieve it,’ which helps explain why so few people feel as if they have done so. Much of it involves passing on to the next generation, ensuring children are happy and unburdened for as long as possible while also preparing them to live their lives. Or it’s about practicing some level of mindfulness, being present in the moment you are in and not worrying over much about the future. Or it’s about hitting par for most of the course.

All of it is reducing anxiety and stress as the most direct pathway to happiness, which certainly calls into question choices about the golf.

Morrione delves into a wide cross-section of immigrants and individuals, from doctors and professionals to a young woman from Bangladesh who directly compares the privation of her youth to opportunity of Dubai where she can actually focus on school because basic needs have been met. For her happiness is nothing more complex than absence of want for the bare necessities. It’s all a matter of perspective. In the process we are introduced to a wider and more complex world within Dubai than many may be aware of all in search of the same goals in life and each unsure how to get it.

There’s more than a little advertising to wade through but as ambiguous as it can be there is truth to take from it. The fact that no one can quite put their finger on what they need for happiness isn’t a gap or a bug. It’s the whole thing.

You Resemble Me

Dina Amer’s turbulent whirlwind of broken emotions and torn hopes doesn’t try to answer the question; it wants to thrust its audience into it, to feel what Hasna went through even as it recognizes the futility of ever actually knowing her.

In France of 2015, in the throes of momentous cultural turmoil and violence, a block of metropolitan Paris was destroyed in an explosion laid at the feet of Hasna Aït Boulahcen – the first reported female suicide bomber as she was called on multiple news reports. Over the days and months that passed interrogations into the life of the party-goer friends called the ‘cowgirl of Paris’ led to questions about how she could have been drawn into the radicalization of the terrorist cell that masterminded the bombing and eventually the realization she was as much a victim as anyone else caught in the blast, trying in vain to escape the group she had fallen into. But still the question remained, how had she ended up there?

Dina Amer’s turbulent whirlwind of broken emotions and torn hopes doesn’t try to answer the question; it wants to thrust its audience into it, to feel what Hasna went through even as it recognizes the futility of ever actually knowing her. Like an electron Hasna is not one person but many, a superposition of acts and events and effects and emotions which can never be fully understood because even to look at her is to change who she was. Pulled from her sister Mariam (Ilona Grimaudo) at a young age and thrust into France’s foster care system, Hasna never develops a concrete sense of self, instead flowing from place to place and situation to situation seeking either escape or return to Mariam. Unable or unwilling to confront her own emotional issues she instead searches for magic talisman to fill the hole in her life, from drugs and dance clubs to an attempt to join the army and finally into religious fundamentalism and extremism.

Following in the footsteps of Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire, Amer replicates Hasna’s confusion of self with literal confusion of self, casting four different actresses (including herself) as the adult woman, switching between them as Hasna flows between the different parts of her life and attempts to keep them from crashing into one another. When Buñuel did it he wanted to showcase something about the unknowableness of women from a purely possessive viewpoint. Amer turns that lens away and back on the world, condemning the vagaries of societies views on women to the point where no one could tell who Hasna actually was, mistakenly naming several different people (many still very much alive) as the dead victim.

It's a chaotic bit of filmmaking, ignoring explanation of background or context to plunge the audience into Hasna’s headspace. She doesn’t know what she’s doing or why, so why should anyone else have such clarity? Nor does Amer stop only with her narrative whiplash, eventually replacing her film with multiple versions of itself as it moves from dramatic recreation into documentary, bringing on Hasna’s real friends and family to explain how hollow the notion of answers or catharsis is. Everyone has their own view of Hasna, everyone sees her as some reflection of what they see in themselves and no one realizes there was unique individual who was both none and all of those things.

Culturally damning without finger pointing or accusation, on both the French and immigrant side, You Resemble Me aims for truth while acknowledging the impossibility of the task. Amer’s questioning without answers is difficult by design, recognizing from the outset that there are no answers that will satisfy anyone, least of all Mariam who cut her sister out of her life and blames herself and that decision for what became of her sister and asks ‘what if things had been different?’ Like everything else around Hasna, there is no answer and there never will be.

8:37 Rebirth

The complexities of redemption and retribution threaten to overwhelm not just the characters of 8:37 Rebirth, but the cast and crew behind them as well.

Somewhere within the spiraling variables of guilt, revenge and redemption mathematician Sergei (Ebrahimi) has spent his life trying to reformulate, the survivor of violence and grad school has become lost within the maze of thought he has built for himself – and he has taken the movie he stars in with him. Seeking a new vector into a story of everyday violence and the effect it has on everyone involved – victim and aggressor alike – co-writer and director Juanita Peters’ focus on external stimuli to work through trauma, be it math or art, is interesting in the abstract but threatens to pull focus from the human beings using them. As Sergei falls further and further into conspiracy and anger the focus shifts from him to his walls full of figures and figurines, revealing the film to be just a phantasm, a quirk of the intellect.

Perhaps it’s the way Peters tells the story, fragmenting the narrative like one of Sergei’s notebooks. He comes to us initially as a loving family man, working on his breakthroughs and trying to teach his precocious son with only hints at what a phone call announcing the release of convicted murderer Jared (Gould) means to him. Peters teases out the revelations behind Sergei’s trauma through fractured flashbacks and subplots around Jared’s own release and attempt to assimilate into a society he hasn’t been a part of in decades. Like Aronofsky’s Pi, math becomes a language of madness rather than cold fact but Sergei isn’t a Max Cohen like truth seeker falling prey to the inner recess of his mind as the core element of his story. It’s a dodge he has built for himself to avoid truth and in that decision lies all the difference as Peters gives few details on either his pain or his delusion until very late.

Instead she reframes, counterpointing Sergei’s algorithm fueled delusion with Jared’s discovery of his inner artist and the freedom from shame or judgment that comes with that. The reductionism of art versus science aside there is real possibility in the contrast to the way they embrace their guilt and distance from society, the different paths their lives have taken and the ways they may escape from their pain. Left to that level of spare focus Rebirth is as good as its name and the inherent drama in it is revelatory. But it’s also piecemeal. More is piled on top of more is piled on top of more and all further and further to the periphery of Sergei and Jared. Even as they struggle with their painful connection they are further encumbered by parole officer John (Owen) who connects the two of them but also has his own internal demons of jealousy and pride to fight against. It becomes a cornucopia of guilt and remorse and pain and violence that pulls focus further away from its scintillating core.

Maybe it was unclear what else could be done with Sergei and Jared apart from their inevitable confrontation. Maybe the lure of melodrama and confusion was too strong, overcoming the pileup of emotions and relationships such a spare story doesn’t need. It would be interesting to see it approached again with the needless parts stripped away and only the center left behind to stand on its own. As it is, it’s all too much; like Sergei, Rebirth is full of good ideas to frequently falls into madness.

8:37 REBIRTH RATING: 6.5/10

8:37 Rebirth was directed by Juanita Peters and Stars Glen Gould, Pasha Ebrahimi, Mark A. Owen and Amy Trefry.

Take the Night

Dark and twisty, Seth McTigue’s Take the Night plumbs the psychological depths of envy and need with plenty of mood even if the plot doesn’t move particularly fast.

There’s nothing worse than planning a birthday party. Creating just the right mixture of expectation and surprise, wrangling attendees, anticipating wants and needs without signaling plans or knowing entirely what the audience wants. It’s like making a movie but with more immediate emotional devastation if it’s not exactly what everyone wants.

William Chang (Huang) has cooked up a doozy for his brother Robert (Li), one that will unravel dark consequences for them and everyone involved. Dark and twisty, Seth McTigue’s Take the Night plumbs the psychological depths of envy and need with plenty of mood even if the plot doesn’t move particularly fast.

Jealous and spiteful, William has never forgiven Robert for being the one to be given total control of the family company, filling their relationship with passive aggressive sniping. He takes that gnawing envy past its darkest limits when he plans a fake kidnapping of Robert as part of his birthday party, giving him a few moments of fear and uncertainty as payment for his easy and unearned privilege. Hiring a group of professional (not to mention poor and desperate) criminals to pull off his prank, with no real thought about outcomes beyond Robert’s immediate fear, William is amazingly surprised when Robert is hurt for real and the criminals use the kidnapping to gain access to the company’s assets. Hurt and envy quickly metastasize into backstabbing and fear as brother turns on brother and friend turns on friend under the lure of sudden wealth.

High-concept thrills gives way to complex character work as McTigue contrasts the relationships of the brothers and the criminals and their underlying fragility. The dichotomy of the wealthy and the poor and how easily desire crosses that seemingly impenetrable class barrier is the heart of Take the Night, mostly through William’s barely concealed condescension of his brother and criminal-in-charge Chad’s (McTigue) attempt to keep his gang together amid the tension of the kidnapping. While William blinds himself to what he already has, Chad is only ever aware of what he doesn’t and what an opportunity it is to get access, even briefly, to the Chang family fortune. As surrounded as he is by the pain money causes, however, he never quite realizes how easily that pain could transfer to himself and his people.

Twisty, a little meandering but with pointed messaging of greed and wealth, writer/director/star McTigue keeps everything together even as his plot attempts to derail itself. His Chad is the depleted conscience of Take the Night, seemingly the only person able to feel the pain of the world and what he is doing to it, even if that empathy isn’t enough to stop him. Huang and Li, by contrast, have to be much more self-involved and oblique in order to protect plot turns, but at the cost of placing them at a remove from the audience’s care. From time to time it’s not always entirely clear what is happening to them.

Quibbles aside, Take the Night is a fine addition to the thriller oeuvre. It slows down to take time with its characters, which keeps it from always showing real care to its plot twists. There are multiple ways to have approached the clever premise, from comedy to action to pure thriller. Perhaps Night’s best surprise is refusing any of those options and making its own identity. A focus on character and strong performances from Li, Huang and Tigue keep the story on the straight and narrow and converging to something more than just tragedy. Hopefully McTigue takes what he’s learned here and returns to the genre – it feels like a real classic is somewhere just in the making. That would make for a nice surprise.

TAKE THE NIGHT RATING: 7/10

Saban Films’ Take the Night was directed by Seth McTigue and Stars Roy Huang, Sam Song Li and Seth Mctigue.

Love in Kilnerry

The romantic comedy has been on an extended downslide over the last two decades as both movie stars declined in value and filmmakers pushed towards more line-crossing comedy that increased humor at the cost of charm.

The romantic comedy has been on an extended downslide over the last two decades as both movie stars declined in value and filmmakers pushed towards more line-crossing comedy that increased humor at the cost of charm. The post-2000s rise of the Judd Apatow school of comedy created some unabashed classics but, intentionally or not, pushed the classic studio romantic comedy into a corner to languish. Attempts have been made to reclaim it, from hazy Hallmark Christmas films to a growing streaming catalog, but the view on what the form is or can be remains split leaving new entrants to the field scrambling to decide which direction to go. Daniel Keith’s inaugural attempt, Love in Kilnerry, attempts to split the difference with its small-town tale of libido gone wild, keeping it from being entirely as charming or as lewd as it needs to discover greatness but finding some real warmth nonetheless.

The sleepy town of Kilnerry in New England is an aging community of fisherman, bars and stationary stores with more elderly than young still living there quietly going about their autumn years. The introduction of a new chemical to the water supply shakes all of that up, however, when the EPA warns the town of an unexpected side effect -- the massive increase of the town’s libido and a fall in inhibitions. As more and more of the town’s residents give over to their newfound desires it falls to the put-upon sheriff (Keith) to keep things together and protect the townspeople from themselves … whether they want him to or not.

The brainchild of writer-director-star Keith, there is a clear understanding from the start that the farther he goes down the rabbit whole of kinks and quirks affecting the townsfolk, the farther he will get from the lighthearted, charming tone he clearly wants. It leaves the film as conflicted as Sheriff O’Reilly himself, wanting to join in with the surrounding festivities but knowing that way madness lies and left with only the option to head out to the middle of the ocean and dance the frustrations away. There are feints towards memorable setups and gags, from the town pastor embracing his inner nudist to the mayors wooing of a local divorcee, but it tends to stop just short of being truly outlandish and never quite lives up to its conceit.

It mostly doesn’t need to. The further Love in Kilnerry delves into romance the less it becomes the center of the film, replaced instead with the strained relationship between prudish O’Reilly and his increasingly liberated father. Keith really is the heart of the film, keeping all of the disparate storylines tied together and willingly playing the straight man in every scenario, but Roger Simon is its soul as the Sheriff’s retired father slowly finding his way to living again, his hair and mustache becoming darker and bushier even as his son falls further and further apart. A reverse Dorian Grey, finding life where his son won’t, Fergal is the embodiment of the idea that letting go of pain and fear is ultimately freeing and necessary.

There’s nothing new or earthshattering in Love in Kilnerry, but there doesn’t need to be either. It’s focus on light romance is increasingly rare in comedy and worth celebrating when it pokes its head above water. Its refusal to lean into the crudest aspects of premise is keeps it from being as funny as it could be, but it also keeps its heart front and center in a way romantic comedy has lost. Hopefully there’s more where this came from.

The Whole Lot

Constraint can be an artists’ best friend. Without the wherewithal for swooping images or lush backdrops the filmmaker is ideally forced into the heart of his piece, scything through obscuring sound design or camera movement to emerge with a treasure of real truth in his or her hands. Forced to discover what their film is really about and present it without trappings it is made irresistible or dies.

Constraint can be an artists’ best friend. Without the wherewithal for swooping images or lush backdrops the filmmaker is ideally forced into the heart of his piece, scything through obscuring sound design or camera movement to emerge with a treasure of real truth in his or her hands. Forced to discover what their film is really about and present it without trappings it is made irresistible or dies.

In practice it dies more often than not. Shorn of their coverings a lot of decent movies are revealed to be hollow in the center. Even more mundane or silly ideas are gussied up to a level of respectability, their art coming entirely from their craft because there’s not much else to them.

On the surface Connor Rickman’s The Whole Lot is the classic example of the form, reducing itself to just a handful of cast members and a single location to get the most from its limited resources, but also discovering what those limitations truly mean. Dialogue heavy and character rich, Matthew Ivan Bennett’s screenplay could easily be mistaken for a stage adaptation rather than the original story it is. A single, nearly real-time conversation between Della (McLoney), her husband Eli (Webb) and estranged brother Jamie (Kramer) over the disposition of their late fathers collection of classic cars unravels into a litany of recrimination and secrets The Whole Lot is a unity of time, place and action that would have made the Greeks stand up in admiration.

Stuck as they are in the garage until an agreement can be made about who gets which vehicles – Della and Eli seek to sell the entire collection to fund their entrepreneurial pursuits while the will restricts Jamie, who actually worked on the cars, to just one vehicle for fear he will fritter it away on drink and drugs – the film itself never comes off as trapped. It speaks to the strength of Bennett’s screenplay and the surety of Rickman’s direction that The Whole Lot never seems slow or ungainly even as it revolves its small cast around into distinct two-character scenes that scratch away at the strange and strained relationships between the trio. Why does Jamie dislike Eli and what is behind his drinking? How has the SIDs death of Della and Eli’s son strained their marriage and why is Eli pushing so hard to sell the cars? Why does Della continually give in to Jamie and is increasing demands even as she sees his instinct for self-destruction take hold of him?